Difference between revisions of "mgh:cyto-1-11"

| Line 267: | Line 267: | ||

* Abundant granular cytoplasm | * Abundant granular cytoplasm | ||

* Indistinct cell borders in clusters | * Indistinct cell borders in clusters | ||

| − | + | {{img3|1-11-2 PPANC-04._Normal_panc_duct.jpg|Normal pancreatic duct}} | |

Key Cytological Features of Ductal Epithelium: | Key Cytological Features of Ductal Epithelium: | ||

Latest revision as of 13:27, July 6, 2020

Contents

The clinical evaluation of patients who present with a biliary stricture, pancreatic cyst or solid mass begins when the patient comes to medical attention due to symptoms, or when a lesion is discovered incidentally during work-up for another reason. Managing these patients is challenging due to the wide variety of options for treatment ranging from observation to surgery. Carcinoma is a clinical concern for patients with newly diagnosed late onset diabetes mellitus or unexplained acute pancreatitis in an older individual.1 Development of jaundice, pruritus or cholestasis not explained by underlying liver or gallbladder disease or choledocholithiasis should initiate an evaluation for neoplasia of the hepaticobiliary tract. 2,3 Abdominal pain that radiates to the back, anorexia, weight loss, steatorrhea, and abnormal liver enzymes are also common presenting symptoms of pancreaticobiliary disease.

There are many imaging modalities that can be used in evaluating the pancreas and biliary tract (Table 1). The general standard “pancreas protocol” begins with a computed tomography (CT) scan, usually multiphase or multidetector CT (MDCT) with contrast. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques including MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and MR angiography (MRA) are used in selected cases such as small lesions, unclear solid versus cystic composition or in search of a connection to the main pancreatic duct in suspected branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms(IPMN) .4,5 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is most useful clinically for providing relief of obstructive jaundice by either plastic or metal biliary stent placement. Brush cytology from biliary strictures or, to a lesser extent, pancreatic duct strictures, is utilized to sample duct strictures. It is only rarely used as a primary tool for establishing the diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma or in the work-up of pancreatic cysts as these lesions are best evaluated with EUS-FNA.

For pancreatic cysts, the most important clinical determination is whether a pancreatic cyst is mucinous or non-mucinous on the one hand, and benign or malignant (high-grade or high-risk cyst) on the other.6 This distinction by imaging alone is quite challenging, but imaging classification systems have been proposed.7 Most patients with inflammatory pseudocysts can be managed medically and serous cysts are benign neoplasms that do not warrant surgical resection unless the patient is symptomatic or the cyst is large (> 4cm)8. Management guidelines have been proposed for suspected mucinous cysts.9 These guidelines base management primarily on clinical and imaging findings with conservative management of small cysts (< 3 cm) occurring in patients without high-risk clinical or imaging findings. Patients with high-risk imaging features or ≥suspicious cytology are triaged to surgery. Patients with worrisome imaging features should be evaluated by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy for further assessment of high-risk features.

For solid masses EUS is used for preoperative staging in patients with suspected pancreatic or biliary tract carcinoma. EUS is particularly useful when CT or MR findings are equivocal, in CT-resectable disease to screen for subtle vascular involvement (especially in borderline surgical candidates), or when unresectable disease is suspected and a tissue diagnosis is needed.10 EUS is better than CT and MR in establishing the presence of vascular invasion, and for detecting small masses, evaluating for tumor involvement of the superior mesenteric and portal veins and for detecting lymph node metastases. 4,11,12

A key advantage of EUS is that EUS-FNA can be performed as an integral part of EUS examination. This allows definitive tissue acquisition and rapid diagnosis. When EUS suggests resectability, EUS-guided biopsy may not be necessary prior to definitive resection. EUS-FNA can confirm the presence of metastatic disease in image detected lymphadenopathy. Patients considered candidates for preoperative neoadjuvant therapy require a definitive tissue diagnosis. Aspiration of pancreatic cysts provides fluid for biochemical, cytological and molecular analysis that help to determine the nature of the cyst and if the patient requires surgical or conservative management.

All specimens submitted to the pathology laboratory are accompanied by a specimen requisition form. This form is a means of communication, not only to the pathologist interpreting the specimen, but also to the laboratory personnel who process the specimen. Often tissue management protocols are in place for certain specimen types and clinical diseases, so this information must be clearly delineated on the requisition form. Additional helpful information specific to the pancreaticobiliary tract includes precise site of the lesion being sampled, the tissue traversed during FNA (stomach or duodenum), the solid or cystic nature of the lesion, the presence or absence of bile duct or pancreatic duct stricture, the size of the lesion and the presence of high-risk or worrisome features. For pancreatic cysts, the configuration of the cyst is vital, e.g. borders, loculations, wall thickness, mural nodules or masses, etc. Clinical suspicion of neuroendocrine tumor or lymphoma should be indicated as tissue for the proper evaluation of these neoplasms requires special handling.

1. Guidelines for the management of patients with pancreatic cancer periampullary and ampullary carcinomas. Gut. Jun 2005;54 Suppl 5:v1-16.

2. Baron TH, Mallery JS, Hirota WK, et al. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation and treatment of patients with pancreaticobiliary malignancy. Gastrointest Endosc. Nov 2003;58(5):643-649.

3. Patel AH, Harnois DM, Klee GG, LaRusso NF, Gores GJ. The utility of CA 19-9 in the diagnoses of cholangiocarcinoma in patients without primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. Jan 2000;95(1):204-207.

4. Midwinter MJ, Beveridge CJ, Wilsdon JB, Bennett MK, Baudouin CJ, Charnley RM. Correlation between spiral computed tomography, endoscopic ultrasonography and findings at operation in pancreatic and ampullary tumours. Br J Surg. Feb 1999;86(2):189-193.

5. Megibow A, Zhou X, Rortterdam H. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: CT versus MR imaging in the evaluation of resectabiilty--report of the radiology diagnostic oncology group. Radiology. 1995(195):327-332.

6. Pitman MB, Brugge WR, Warshaw AL. The value of cyst fluid analysis in the pre-operative evaluation of pancreatic cysts. J Gastrointest Oncol. Dec 2011;2(4):195-198.

7. Sahani DV, Kadavigere R, Saokar A, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Brugge WR, Hahn PF. Cystic pancreatic lesions: a simple imaging-based classification system for guiding management. Radiographics. Nov-Dec 2005;25(6):1471-1484.

8. Tseng JF, Warshaw AL, Sahani DV, Lauwers GY, Rattner DW, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: tumor growth rates and recommendations for treatment. Ann Surg. 2005;242(3):413-419; discussion 419-421.

9. Tanaka M, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Adsay V, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. May-Jun 2012;12(3):183-197.

10. Palazzo L, Roseau G, Gayet B, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis and staging of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Results of a prospective study with comparison to ultrasonography and CT scan. Endoscopy. 1993;25:143-150.

11. Howard TJ, Chin AC, Streib EW, Kopecky KK, Wiebke EA. Value of helical computed tomography, angiography, and endoscopic ultrasound in determining resectability of periampullary carcinoma. Am J Surg. Sep 1997;174(3):237-241.

12. Legmann P, Vignaux O, Dousset B, et al. Pancreatic tumors: comparison of dual-phase helical CT and endoscopic sonography. AJR. Am. J. Roentgenol. May 1998;170(5):1315-1322.

Techniques for Cytologic Sampling of Pancreatic and Bile Duct Lesions1

Major developments in the diagnosis and management of patients with pancreaticobiliary diseases have stemmed from improvements in sampling of the pancreas and biliary system, principally through the advent of EUS-FNA 2. EUS-FNA is now the procedure of choice for establishing a diagnosis of pancreatic malignancy, and the recent development of core needles that can be used with EUS will further improve diagnostic accuracy.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is the traditional and simplest method of obtaining a cytology specimen of a biliary stricture3. Brush cytology has a much better yield than bile aspiration alone, and brushing cytology provides a more accurate diagnosis than directed focal biopsy because the entire surface area of the stricture is sampled by the brush4. Tissue can be smeared on a slide or released from the brush in preservative solutions for liquid-based processing. 5 Biopsies are often used to supplement brush cytology. When comparing brushing, standard forceps and mini-forceps methods of sampling, mini-forceps biopsy provided significantly better sensitivity and overall accuracy compared with cytology brushing and standard forceps biopsy. 6 Needle biopsy of biliary strictures and masses can also be performed with fluoroscopic guidance 7. Endoscopic cholangioscopy is another technique performed using a dedicated, small diameter endoscope that is placed through the instrument channel of a duodenoscope. Finally, EUS-FNA of a bile duct mass may also be used as a technique to establish the diagnosis of malignancy.

EUS-FNA of pancreatic masses requires linear endosonographic instruments 8. The appropriate gauge EUS needle should be selected for the procedure based on the vascularity of the target lesion, the difficulty in accessing the lesion, and the type of tissue needed for a diagnosis. Simple aspiration needles (usually 22- or 25-gauge) are used in the vast majority of biopsies and provide similar cytologic yield 9. Highly vascular lesions such as neuroendocrine tumors and metastatic renal cell carcinoma as well as lesions of the uncinate process should be aspirated with a 25-gauge needle. Smaller gauge needles are easier to use and generally safer. Mucinous cysts are aspirated with 22-gauge needles because of the high viscosity of the cyst fluid. Core biopsy and Trucut needles (19-gauge) are used for fibrotic and stromal rich lesions such as autoimmune pancreatitis. Small gauge core biopsy needles have recently been made available and are often used when standard aspiration techniques do not provide a diagnostic tissue. FNA of cystic lesions one passage of the needle should be used to evaluate a cyst and high suction will aid in the rapid emptying of the cyst. Mural nodules or adjacent masses should be targeted or aspirated separately.

Whenever possible, rapid on site evaluation (ROSE) of cytology should be used in FNAs of solid masses since it reduces the frequency of false-negative FNAs, particularly in the evaluation of pancreatic masses 10. Without ROSE, approximately, 5 passes of a pancreatic mass are needed to ensure adequate sampling. ROSE is not advised for FNAs of cysts unless there is a solid component that provides tissue for direct smears. Aspirated cyst fluid should be carefully triaged for cytology, biochemical testing (CEA and amylase), and molecular testing.

1. Brugge W, Dewitt J, Klapman JB, et al. Techniques for cytologic sampling of pancreatic and bile duct lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. Feb 19 2014.

2. Yoon WJ, Brugge WR. Endoscopic evaluation of bile duct strictures. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. Apr 2013;23(2):277-293.

3. Ferrari AP, Lichtenstein DR, Slivka A, Chang C, Carr-Locke DL. Brush cytology during ERCP for the diagnosis of biliary and pancreatic malignancies. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:140-145.

4. Ung KA, Ljung A, Wagermark J, et al. Brush cytology is superior to biopsies obtained by a new device in bile duct strictures. Hepatogastroenterology. Apr-May 2007;54(75):664-668.

5. Vadmal MS, Byrne-Semmelmeier S, Smilari TF, Hajdu SI. Biliary tract brush cytology. Acta Cytol. Jul-Aug 2000;44(4):533-538.

6. Draganov PV, Chauhan S, Wagh MS, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of conventional and cholangioscopy-guided sampling of indeterminate biliary lesions at the time of ERCP: a prospective, long-term follow-up study. Gastrointest Endosc. Feb 2012;75(2):347-353.

7. Howell DA, Beveridge RP, Bosco J, Jones M. Endoscopic needle aspiration biopsy at ERCP in the diagnosis of biliary strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. Sep-Oct 1992;38(5):531-535.

8. Vilmann P, Saftoiu A. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy: equipment and technique. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. Nov 2006;21(11):1646-1655.

9. Lee JH, Stewart J, Ross WA, Anandasabapathy S, Xiao L, Staerkel G. Blinded prospective comparison of the performance of 22-gauge and 25-gauge needles in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of the pancreas and peri-pancreatic lesions. Dig. Dis. Sci. Oct 2009;54(10):2274-2281.

10. Collins BT, Murad FM, Wang JF, Bernadt CT. Rapid on-site evaluation for endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy of the pancreas decreases the incidence of repeat biopsy procedures. Cancer Cytopathol. Sep 2013;121(9):518-524.

Standardized Terminology and Nomenclature 1

The proposed terminology scheme has six categories (Table 2). New and somewhat controversial is the category “Neoplastic” that is divided into clearly “benign” neoplasms and “other” neoplasms. Using a standardized terminology and nomenclature system provides intra- and interdepartmental guidance for diagnosis and attempts to correlate the diagnosis with our current understanding of the lesion's biological behavior and management recommendations. Interpretation categories do not have to be used, but some pathology laboratory information systems require them, and such categorization may aide in clinical and translational research.

Category I. Non-Diagnostic

A non-diagnostic cytology specimen is one that provides no diagnostic or useful information about the solid or cystic lesion sampled; for example, an acellular aspirate of a cyst without evidence of a mucinous etiology by cytology and ancillary testing.1 Cellular atypia precludes a non-diagnostic report regardless of the cellularity. The clinical and imaging context should be taken into consideration when assessing whether a sample is adequate. The absence of "epithelial cells" in the sample does not necessarily make a specimen non-diagnostic. A pseudocyst, for example, lacks an epithelial cyst lining by definition, and thick colloid-like mucin without epithelial cells may be aspirated from mucinous cysts, but this finding or an elevated CEA level in the cyst fluid, is sufficient to support an interpretation of a neoplastic mucinous cyst. 2-4

Category II. Negative (for malignancy)

A negative cytology sample is one that contains adequate cellular and/or extracellular tissue to evaluate or define a lesion that is identified on imaging. When using the negative category one should give a specific diagnosis when practical; for example, pancreatitis (acute, chronic and autoimmune), pseudocyst and lymphoepithelial cyst.1 Benign pancreaticobiliary tissue in the setting of vague fullness and no discrete mass also qualifies as a negative interpretation. A negative interpretation with a descriptive diagnosis implies that the sample is adequately cellular and that no cytological atypia is present. A “negative” report with a descriptive diagnosis such as "mucinous debris of uncertain origin (lesional versus gastrointestinal contamination)" is reasonable.

Category III. Atypical

The atypical category is appropriate when cells display cytoplasmic, nuclear, or architectural features inconsistent with normal or reactive cellular changes, and that are insufficient to classify the cells as a neoplasm or suspicious for a high-grade malignancy. The category is heterogeneous and includes cases with reactive changes, low cellularity specimens, premalignant changes (dysplasia) and cases assigned to this category due to observer caution in diagnosis. In addition, the cytological findings may be suggestive but not diagnostic of a low-grade neoplasm due to insufficient tissue for confirmation of a specific diagnosis. Brushing cytology yielding atypical biliary epithelium remains in this category since premalignant lesions of the biliary tract have not been as well defined with correlative management algorithms.

Category IV. Neoplastic

IVA. Neoplastic: Benign

This interpretation category connotes the presence of a cytological specimen sufficiently cellular and representative, with or without the context of clinical, imaging, and ancillary studies, to be diagnostic of a benign neoplasm. The most commonly encountered benign neoplasm of the pancreas is serous cystadenoma. Other benign neoplasms of the pancreas such as cystic teratoma and schwannoma are extremely rare and are also placed in this category.

IVB. Neoplastic: Other

This interpretation category defines a neoplasm that is either premalignant such as IPMN or mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN) with low, intermediate or high-grade dysplasia using cytological criteria, or a low-grade malignant neoplasm such as well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNET) or solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN).

This category represents the most controversial aspect of this terminology proposal. The rationale for this proposed category relates the desire to standardize and correlate the cytological nomenclature with the 2010 WHO terminology classification that maintains the nomenclature for both PanNET and SPN as "neoplasms" rather than carcinomas, and to take into consideration the increasingly conservative management approaches for many of the lesions.

These "other" neoplasms are either pre-invasive, premalignant neoplasms (IPMN and MCN with low, intermediate or high-grade dysplasia) or demonstrate low-grade malignant behavior (PanNET and SPN), and, as such, warrant distinction from aggressive, high-grade malignancies (most notably ductal adenocarcinoma). All of the tumors in this category are clearly neoplastic, and even though some are low-grade malignant, the heading “Neoplastic: Other” is an accurate and reasonable generic term that accurately reflects the pre-operative cytological terminology and does not define the neoplasm as benign or malignant. The cytological categories of “atypical” and “suspicious for malignancy” connote an indeterminate interpretation and do not relate the detection of a neoplasm, which could lead to unnecessary repeat biopsy.

The cytological interpretation of PanNET indicates a well-differentiated neoplasm. Although it is now widely accepted that well-differentiated PanNETs all have malignant potential5, many PanNET are very slow growing, and even curable if caught at an early stage, and some are detected incidentally in asymptomatic, elderly patients. To distinguish PanNETs from highly aggressive malignant neoplasms and to offer management flexibility in elderly patients with small, asymptomatic tumors where the risk to benefit ratio of surgery is high compared to conservative management, PanNETs are placed in this category rather than the malignant category. Convincing a patient that conservative management of their incidental 1 cm PanNET is the best option for them is virtually impossible when diagnosed by cytology as malignant.

Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm is a low-grade malignancy but with a small local recurrence rate and low metastatic potential. 6 For these reasons coupled with the fact that the tumor is called a "neoplasm" and not carcinoma, it is included in this Neoplastic: Other category.

The two primary neoplastic mucinous cysts of the pancreas include IPMN and MCN. Premalignant cysts are lined by low, intermediate or high-grade dysplasia; malignant counterparts require invasive carcinoma. Atypia less than overtly malignant is included in this category of Neoplastic: Other. Distinguishing the atypia in these cysts is challenging using a 4 tiered system, and it is not always possible to distinguish high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma, or intermediate-grade dysplasia and high-grade dysplasia. A two-tiered system of low-grade (low-grade and intermediate-grade dysplasia) and high-grade (high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma) epithelial atypia provides the best information for clinical management.7-10 A diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (positive or malignant category) requires unequivocal features of adenocarcinoma.

Category IV. Suspicious (for Malignancy)

A specimen is suspicious for malignancy when some but an insufficient number of the typical features of a specific malignant neoplasm, mainly pancreatic adenocarcinoma, are present. The cytological features raise a strong suspicion for malignancy, but the findings are qualitatively and/or quantitatively insufficient for a conclusive diagnosis, or tissue is not present for ancillary studies to define a specific neoplasm. The morphologic features must be sufficiently atypical that malignancy is considered more probable than not. 1

This category of “suspicious for malignancy” generally refers to pancreatic adenocarcinoma since most malignancies in the pancreas are ductal adenocarcinoma, but this category is used for all high-grade, aggressive malignancies. The suspicious category is an appropriate classification for aspirates that produce a "solid-cellular" clearly neoplastic epithelial proliferation which includes PanNET, acinar cell carcinoma, pancreatoblastoma and SPN in the differential diagnosis, but which has insufficient tissue for confirmatory ancillary studies necessary to make a specific diagnosis. This category has a very high positive predictive value for malignancy.11-13 The risk of malignancy for brushing specimens designated “suspicious for malignancy” is approximately 80% and 96%.14

Category VI. Positive or Malignant

This category includes a group of neoplasms that unequivocally display malignant cytological characteristics including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and its variants, cholangiocarcinoma, acinar cell carcinoma, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma (small cell and large cell), pancreatoblastoma, lymphomas, sarcomas and metastases to the pancreas.

Since 9 of 10 malignancies in the pancreas are conventional ductal adenocarcinoma, the "positive" or "malignant" category is often related to this neoplasm. The specificity of a positive or malignant interpretation for both pancreatic FNA and biliary brushing is very high, >90-95% in most studies 11,15-22. Relying on strict criteria contributes to this high specificity at the expense of sensitivity. Rapid on site evaluation of solid mass lesion FNAs contributes to diagnostic yield 23-25.

1. Pitman MB, Centeno BA, Ali SZ, et al. Standardized terminology and nomenclature for pancreatobiliary cytology: The Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology guidelines. Diagn Cytopathol. Feb 19 2014.

2. Brugge WR, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E, et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. May 2004;126(5):1330-1336.

3. Cizginer S, Turner B, Bilge AR, Karaca C, Pitman MB, Brugge WR. Cyst Fluid Carcinoembryonic Antigen Is an Accurate Diagnostic Marker of Pancreatic Mucinous Cysts. Pancreas. Jul 14 2011;40(7):1024-1028.

4. van der Waaij LA, van Dullemen HM, Porte RJ. Cyst fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions: a pooled analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. Sep 2005;62(3):383-389.

5. Klimstra DS. Pathology reporting of neuroendocrine tumors: essential elements for accurate diagnosis, classification, and staging. Semin Oncol. Feb 2013;40(1):23-36.

6. Kloppel G, Hruban R, Klimstra D, et al. Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. In: Bosman F, Carneiro F, Hruban R, Theise N, eds. 4th ed. Sterling: Stylus Publishing, LLC; 2010:327-330.

7. Pitman MB, Centeno BA, Daglilar ES, Brugge WR, Mino-Kenudson M. Cytological criteria of high-grade epithelial atypia in the cyst fluid of pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Cancer Cytopathol. Jan 2014;122(1):40-47.

8. Pitman MB, Centeno BA, Genevay M, Fonseca R, Mino-Kenudson M. Grading epithelial atypia in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: An international interobserver concordance study. Cancer Cytopathol. Dec 2013;121(12):729-736.

9. Pitman MB, Genevay M, Yaeger K, et al. High-grade atypical epithelial cells in pancreatic mucinous cysts are a more accurate predictor of malignancy than "positive" cytology. Cancer Cytopathol. Oct 7 2010;118:434-440.

10. Pitman MB, Lewandrowski K, Shen J, Sahani D, Brugge W, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Pancreatic cysts: preoperative diagnosis and clinical management. Cancer Cytopathol. Feb 25 2010;118(1):1-13.

11. Bhutani MS, Hawes RH, Baron PL, Sanders CA, van VA, Osborne. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration of malignant pancreatic. Endoscopy. 1997;29(9):854-858.

12. Faigel DO, Ginsberg GG, Bentz JS, Gupta PK, Smith DB, Kochman ML. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided real-time fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the pancreas in cancer patients with pancreatic lesions. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(4):1439-1443.

13. Eloubeidi MA, Jhala D, Chhieng DC, et al. Yield of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy in patients with suspected pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. Oct 25 2003;99(5):285-292.

14. Layfield LJ, Schmidt RL, Hirschowitz SL, Olson MT, Ali SZ, Dodd LL. Significance of the diagnostic categories "atypical" and "suspicious for malignancy" in the cytologic diagnosis of solid pancreatic masses. Diagn Cytopathol. Feb 28 2014.

15. Layfield LJ, Wax TD, Lee JG, al e. Accuracy and morphologic aspects of pancreatic and biliary duct brushings. Acta Cytol. 1995;39:11-18.

16. Turner BG, Cizginer S, Agarwal D, Yang J, Pitman MB, Brugge WR. Diagnosis of pancreatic neoplasia with EUS and FNA: a report of accuracy. Gastrointest Endosc. Jan 2010;71(1):91-98.

17. Ylagan LR, Edmundowicz S, Kasal K, Walsh D, Lu DW. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration cytology of pancreatic carcinoma: a 3-year experience and review of the literature. Cancer. Dec 25 2002;96(6):362-369.

18. Ylagan LR, Liu LH, Maluf HM. Endoscopic bile duct brushing of malignant pancreatic biliary strictures: retrospective study with comparison of conventional smear and ThinPrep techniques. Diagn Cytopathol. Apr 2003;28(4):196-204.

19. Eloubeidi M, Chen V, Eltoum I, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of patients with suspected pancreatic cancer: diagnostic accuracy and acute and 30-day complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2663-2668.

20. Eloubeidi MA, Tamhane A. EUS-guided FNA of solid pancreatic masses: a learning curve with 300 consecutive procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. May 2005;61(6):700-708.

21. Adamsen S, Olsen M, Jendresen MB, Holck S, Glenthoj A. Endobiliary brush biopsy: Intra- and interobserver variation in cytological evaluation of brushings from bile duct strictures. Scand J Gastroenterol. May 2006;41(5):597-603.

22. Volmar KE, Vollmer RT, Routbort MJ, Creager AJ. Pancreatic and bile duct brushing cytology in 1000 cases: review of findings and comparison of preparation methods. Cancer. Aug 25 2006;108(4):231-238.

23. Hebert-Magee S, Bae S, Varadarajulu S, et al. The presence of a cytopathologist increases the diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis. Cytopathology. Jun 2013;24(3):159-171.

24. Klapman JB, Logrono r, Dye CE, Waxman I. Clinical impact of on-site cytopathology interpretation on endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(6):1289-1294.

25. da Cunha Santos G, Ko HM, Saieg MA, Geddie WR. "The petals and thorns" of ROSE (rapid on-site evaluation). Cancer Cytopathol. Jul 3 2012.

Basic cytomorphology

|

||

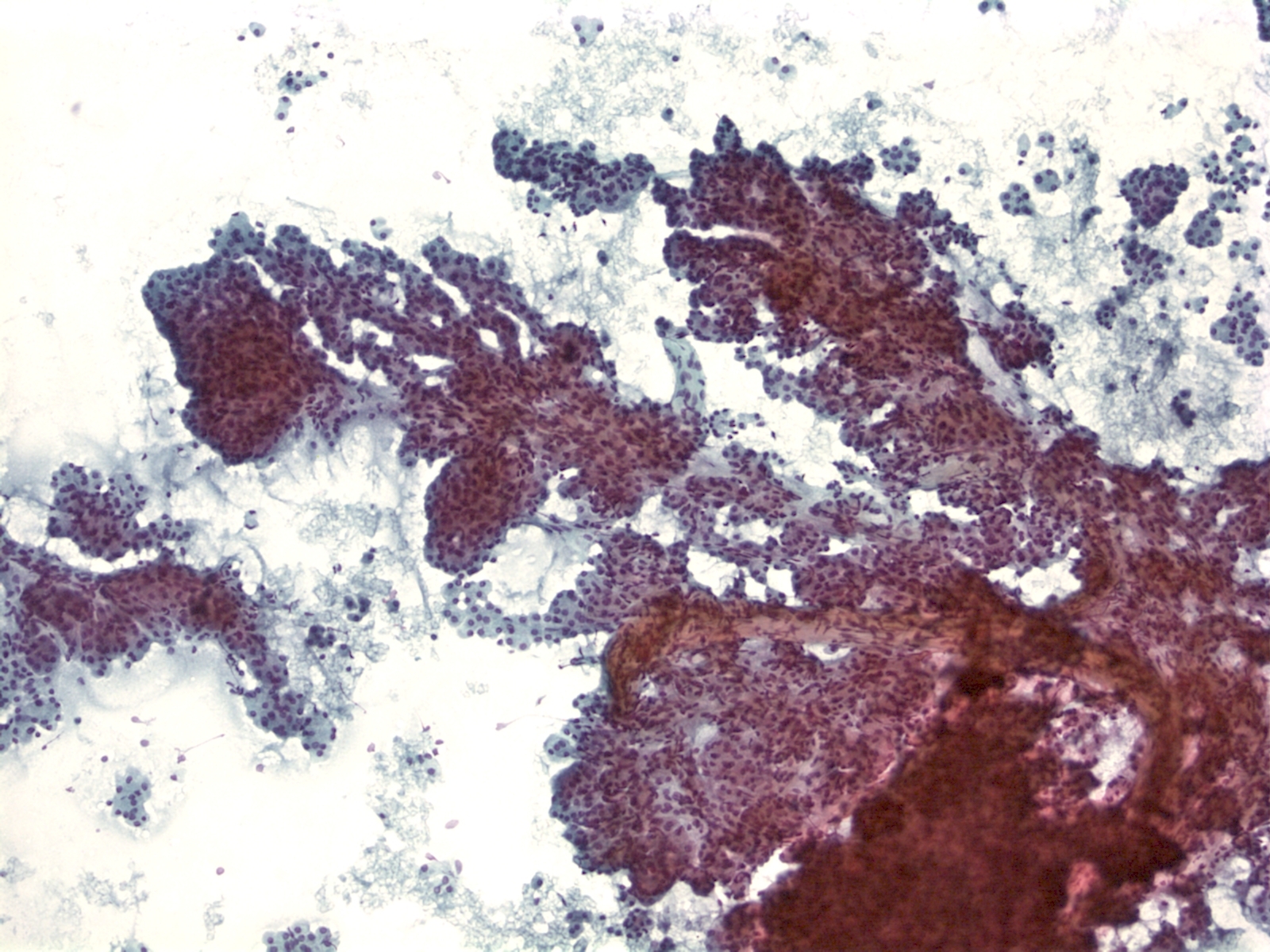

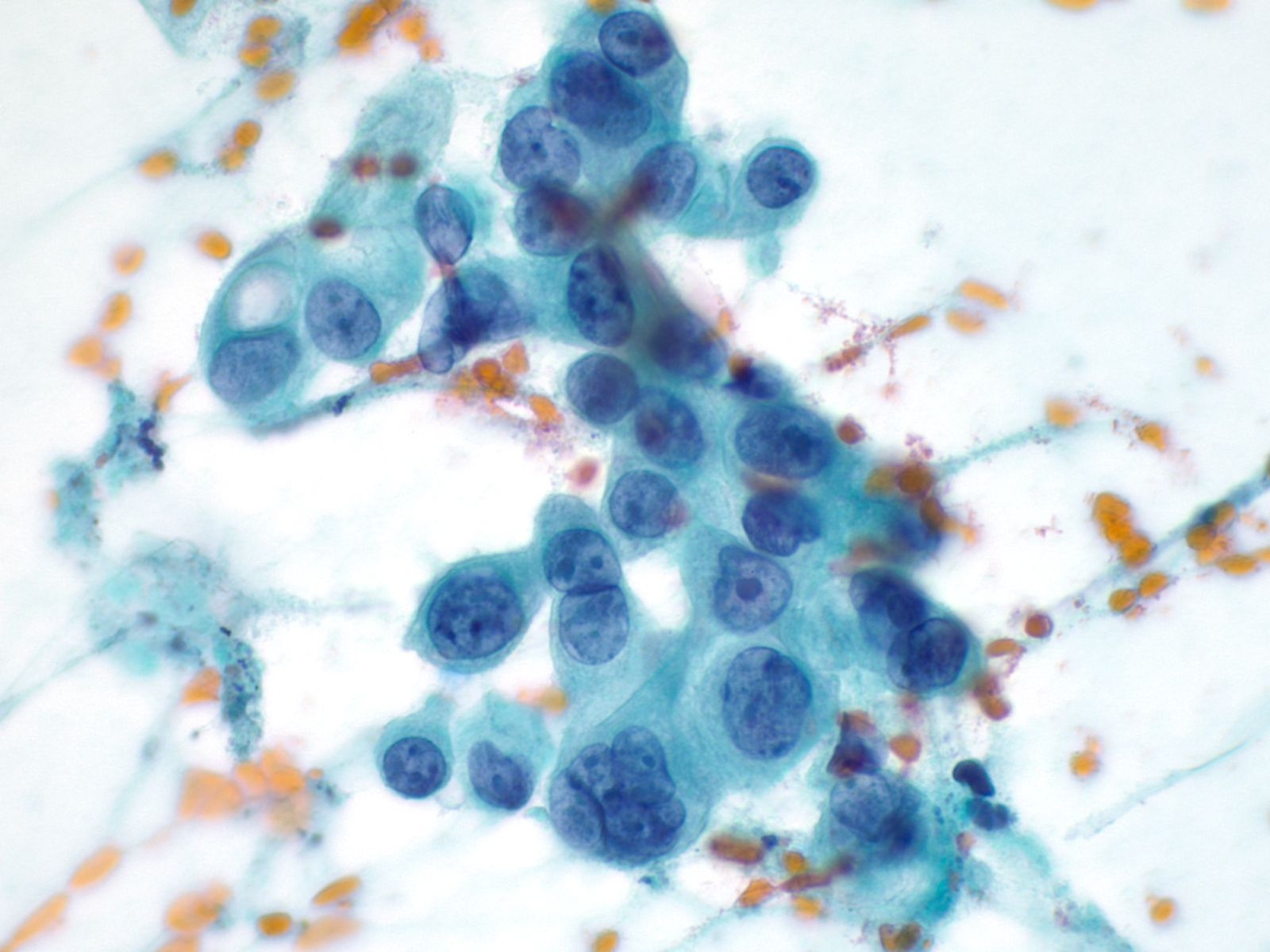

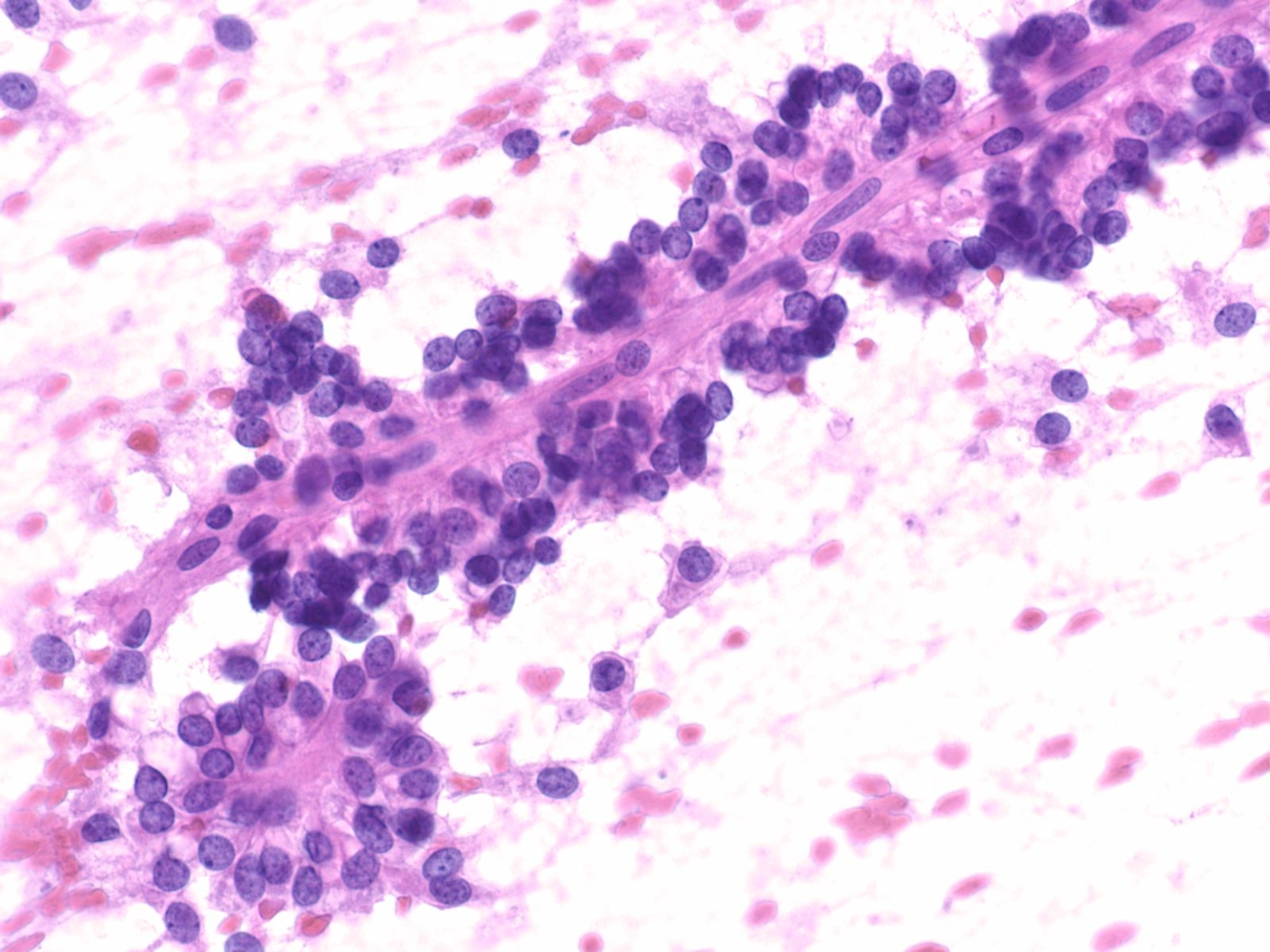

Benign Pancreas – PPANC4-04 Key Cytological Features of benign acinar cells:

- Cohesive, grape-like aggregates singly and attached to fibrovascular stroma

- Scattered stripped naked nuclei

- Basally located round nucleus

- Finely granular chromatin

- Small nucleolus; larger in reactive acinar cells

- Abundant granular cytoplasm

- Indistinct cell borders in clusters

|

||

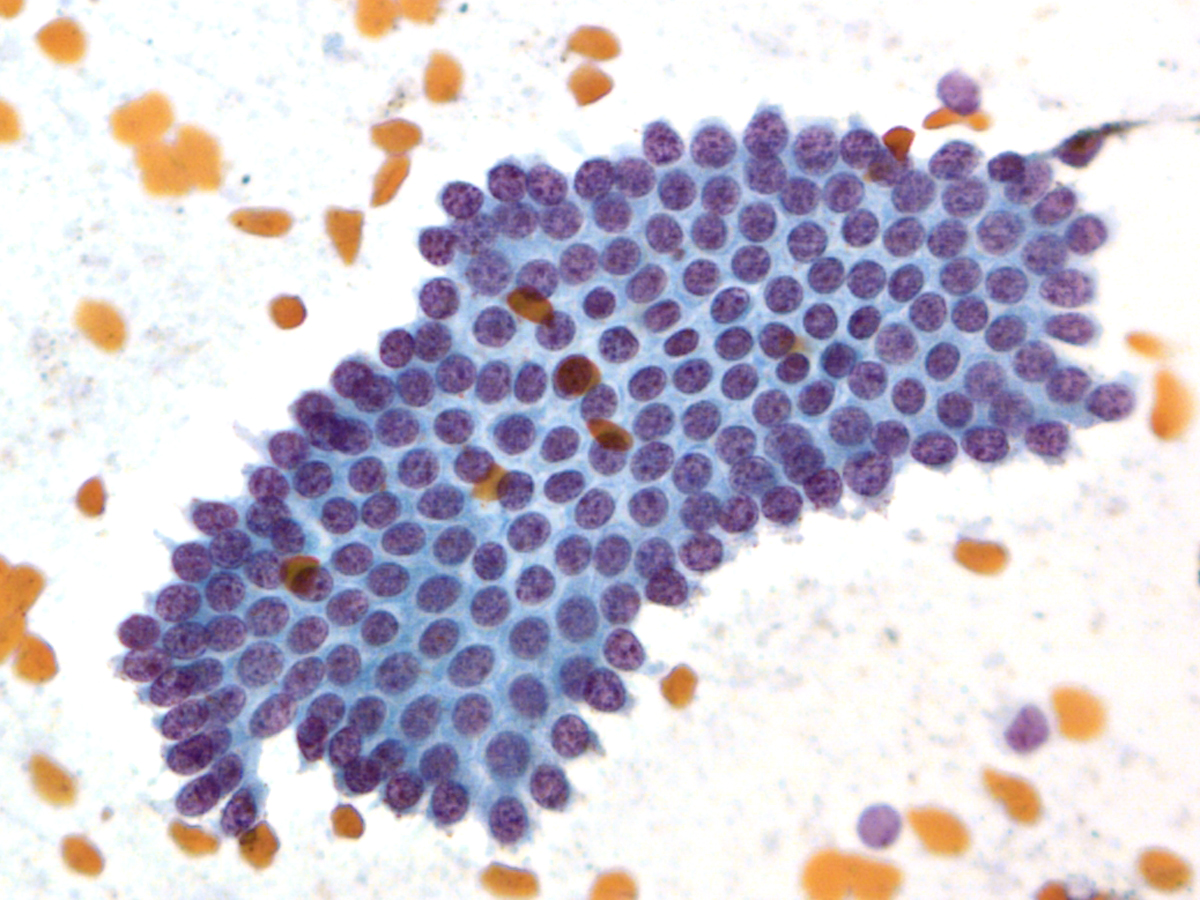

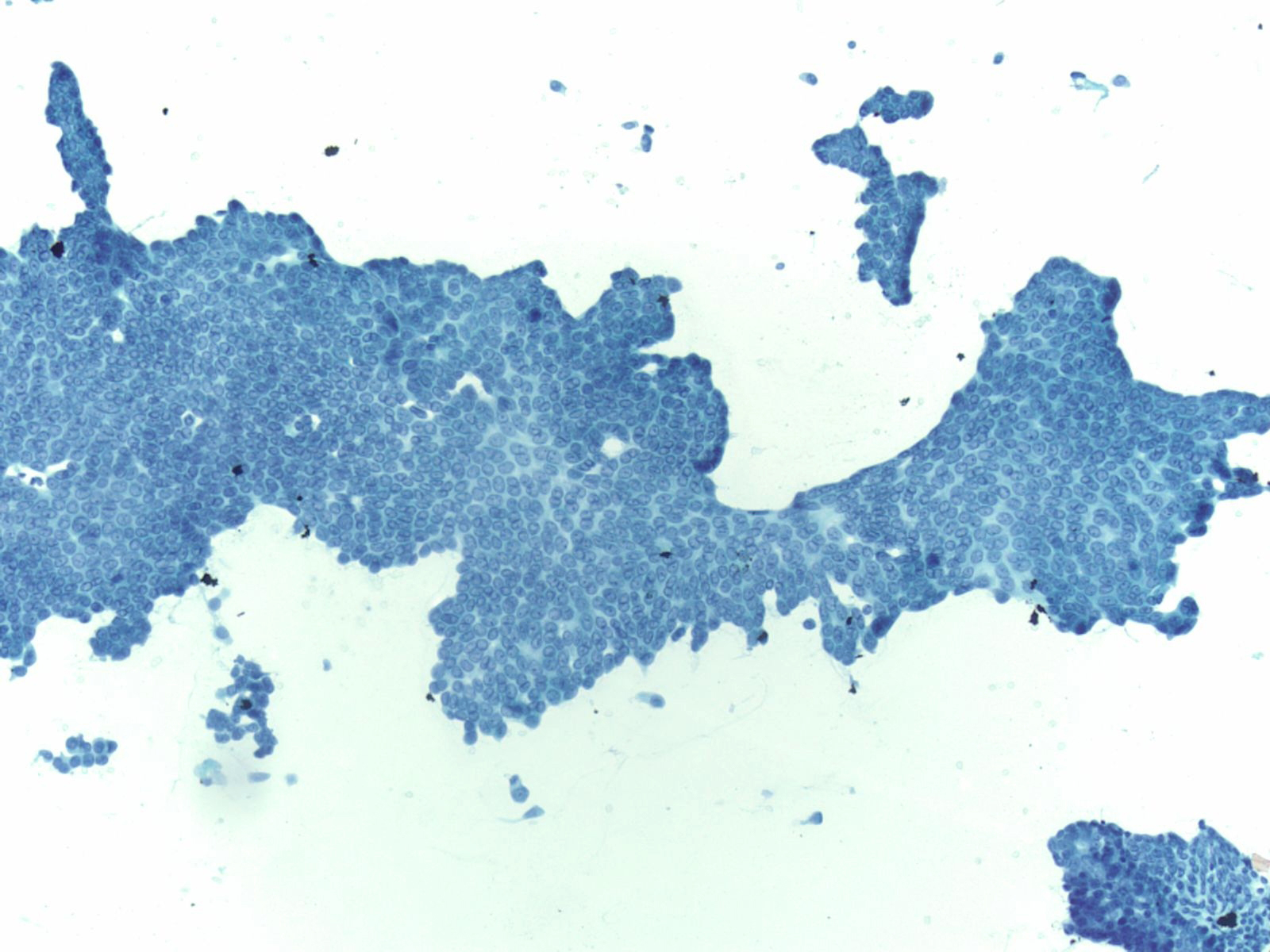

Key Cytological Features of Ductal Epithelium:

- Flat, cohesive sheets with even nuclear spacing within sheets

- Uniform, on-edge "picket-fence" arrangements

- Round to oval nuclei with fine, even chromatin

- Inconspicuous nucleoli

- Non-mucinous cytoplasm

|

||

EUS Contaminants

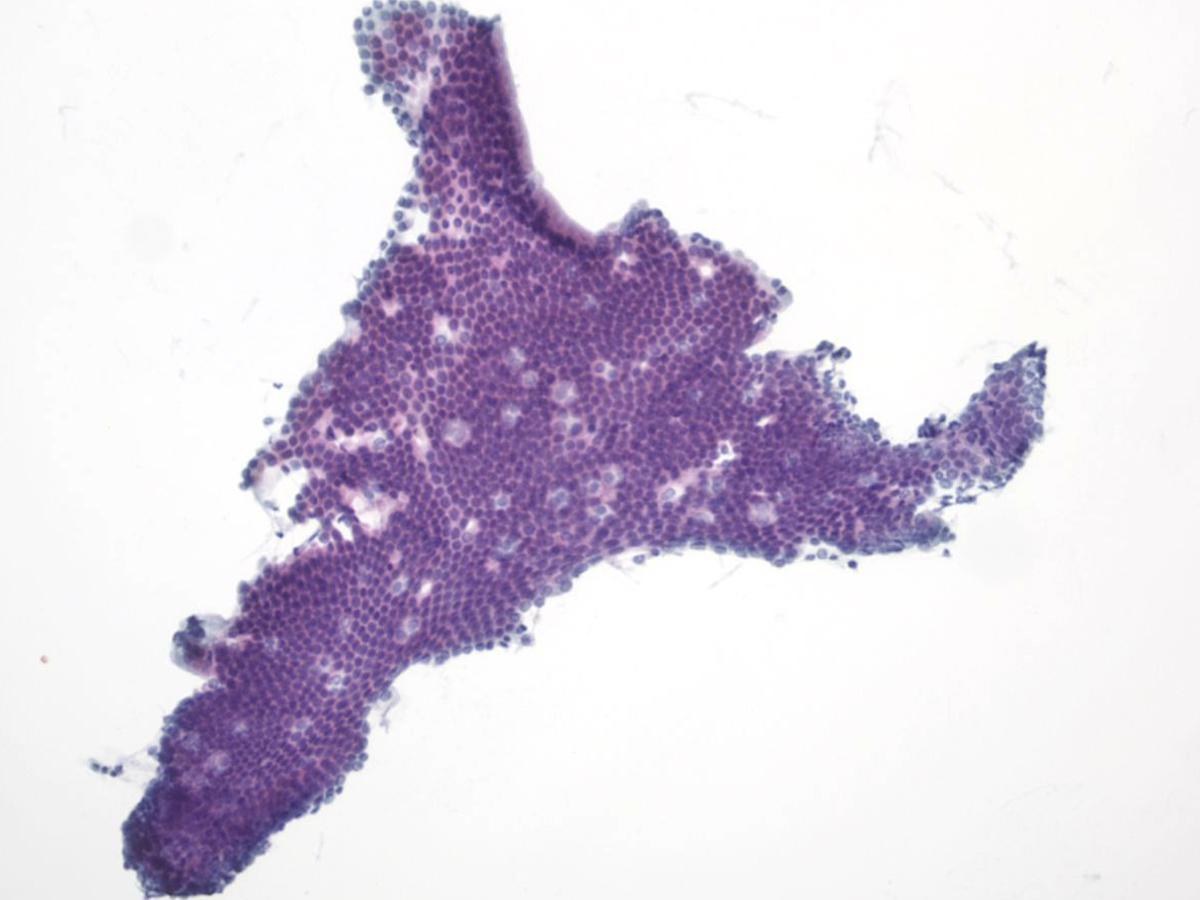

Duodenal Epithelium– MN05-N08394

- Flat and cohesive monolayered sheet with a honeycomb pattern; occasionally papillary groups (intact villi), smaller groups and single cells

- Non-mucinous glandular cells with brush border

- Sporadically placed goblet cells appearing as “fried eggs” with a sheet

- Lymphocytes (“sesame seeds”) in the epithelium

|

||

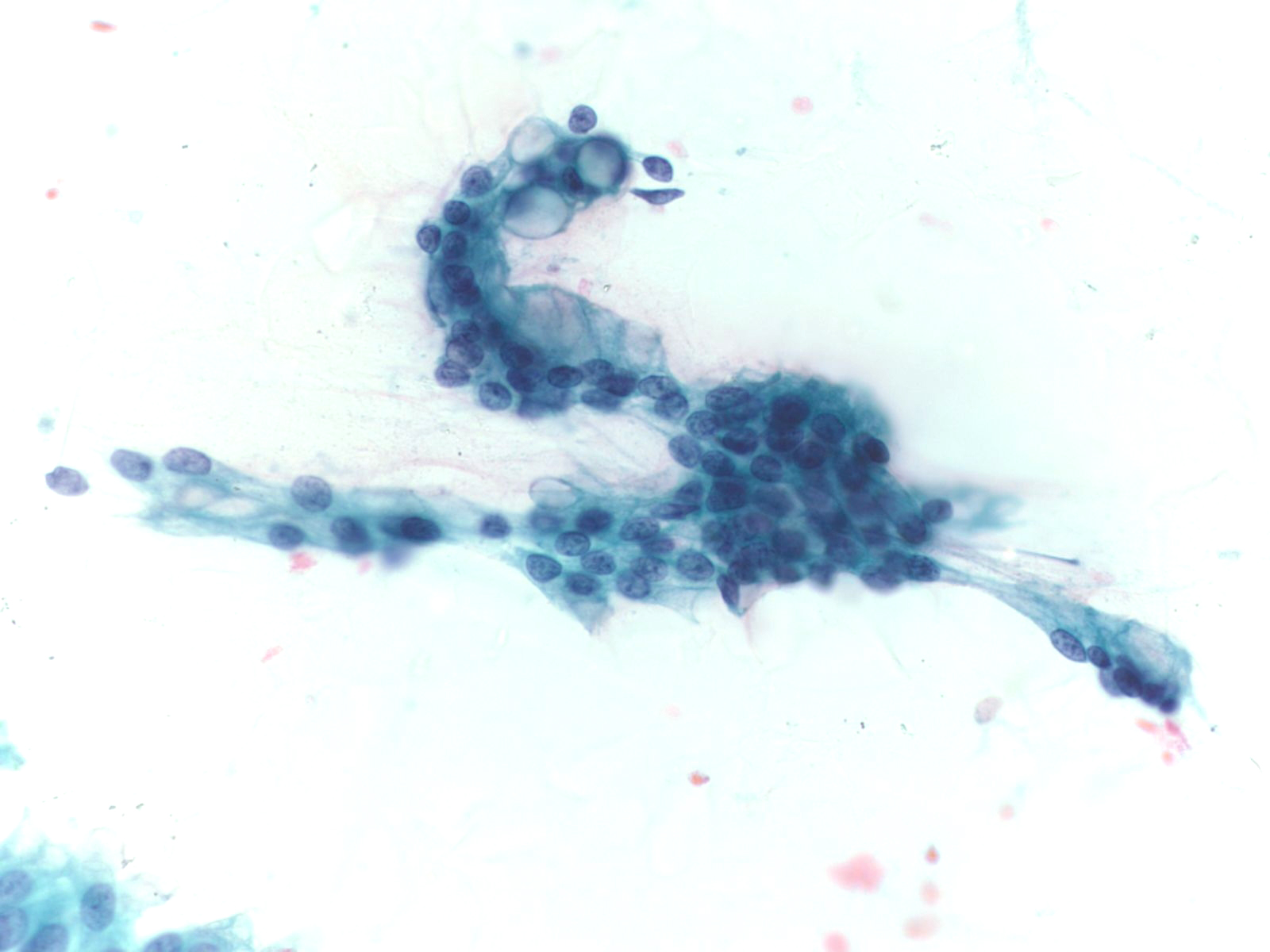

Gastric Epithelium– N13-6431

- Small sheets, strips and occasionally single cells and gastric pits

- Visible mucin in foveolar cells, often apical mucin cups

- Grooved naked nuclei, typically floating in extracellular mucin

Ductal Adenocarcinoma

- Incidence: 11 per 100,000 ; 4th leading cause of cancer death in men and women

- Age, Gender: Peak incidence 7th to 8th decade; M>F by 30%

- Prognosis and Therapy: 5-year survival rate is 3-4%. Surgical resection is the treatment of choice.

- Radiological Features: Hypodense mass with a poorly defined periphery and often a “double duct sign” from dilatation of both the pancreatic and bile ducts.

Key Cytologic Features: Ductal Adenocarcinoma

|

||

High Grade Adenocarcinoma – PPAN4-06

- Glandular smear pattern with ductal cells in variable amounts

- Three-dimensional groups with nuclear crowding, overlap and loss of polarity

- Obvious nuclear membrane irregularities, hyperchromasia, coarse chromatin and prominent nucleoli

- Mitosis, necrosis and dyscohesion with single intact malignant cells

|

||

Well-Differentiated Adenocarcinoma – PPAN3-29

- Loss of honeycomb architecture with nuclear crowding, overlapping, loss of polarity and uneven spacing ("drunken honeycomb")

- Nuclear area variation (>4:1) within a single group of cells

- Chromatin clearing and/or peripheral clumping (parachromatin clearing)

- Abundant cytoplasmic mucin

- Nuclear contour irregularities, often subtle

Neuroendocrine Tumor –MN07-R09706 and N13-6431

- Incidence: ~2-5% of pancreatic neoplasms; ~50% functional and 50% nonfunctional

- Age, Gender: Any age but most between 40-60 years; M=F

- Prognosis and Therapy: Small neoplasms without adverse prognostic features are curable by surgical resection; prognosis is related to tumor size, mitotic rate, necrosis, extrapancreatic invasion, vascular invasion, and nodal or distant metastases

- Radiological Features: Solid, well-circumscribed masses, usually small (<2cm), but may be large (>6cm); can be cystic

|

||

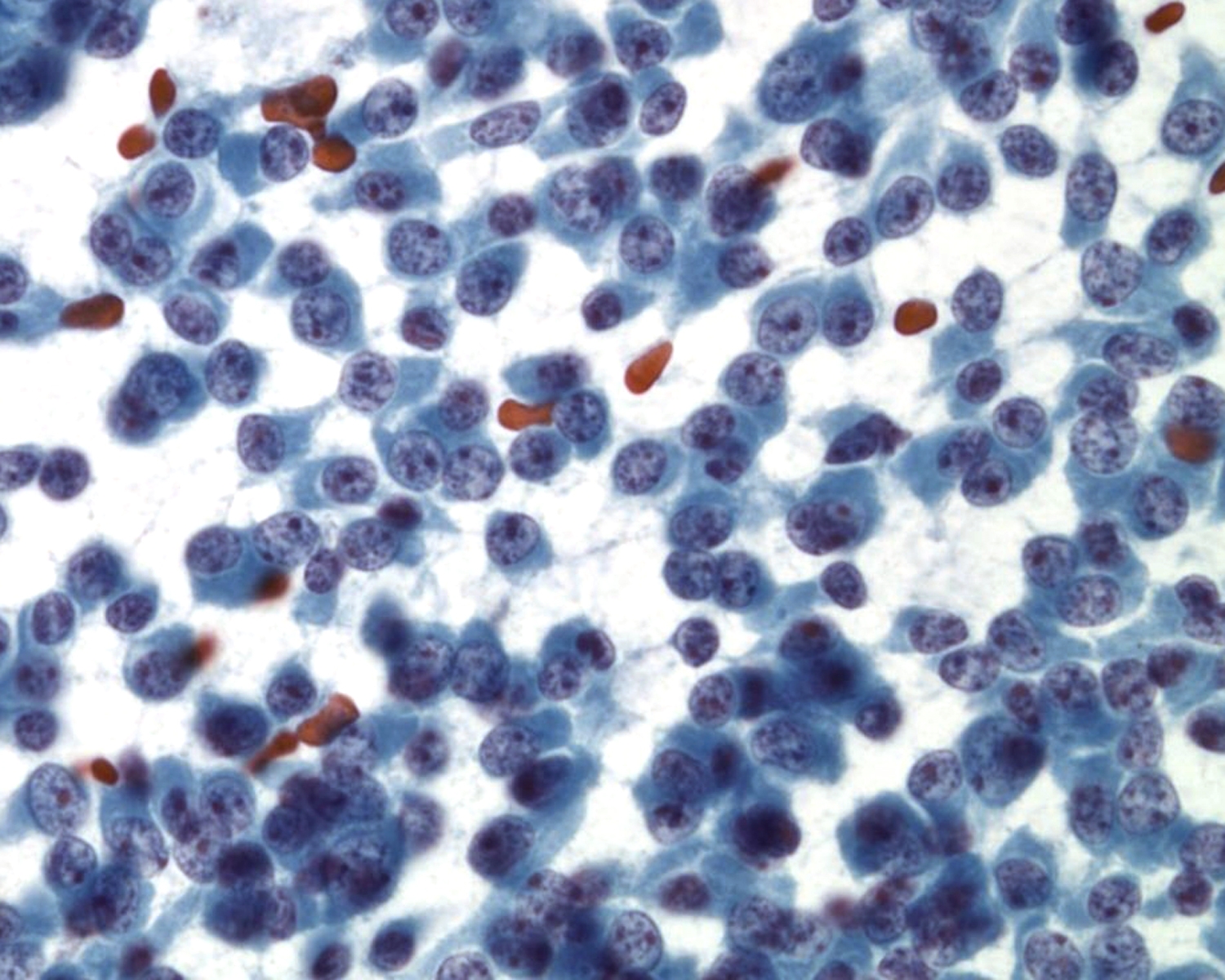

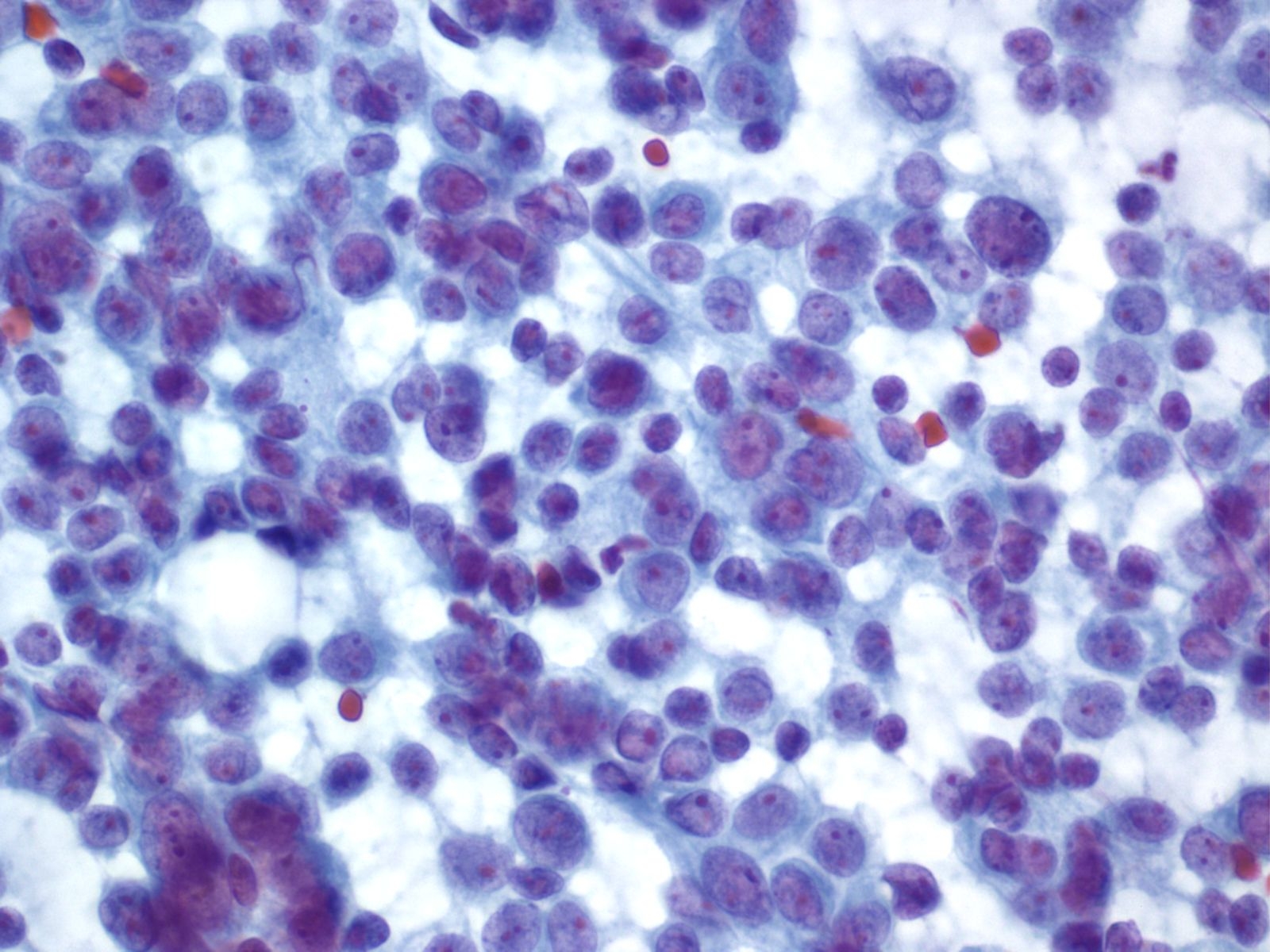

Key Cytological Features: Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor

- Discohesive, single cell "solid-cellular "smear pattern

- Uniform, monotonous population of cells with plasmacytoid features

- Coarse, speckled, “salt and pepper” chromatin pattern

- Nucleoli may be prominent

- Dense, finely granular cytoplasm

Acinar Cell Carcinoma – PAN2-036

- Incidence: ~1-2% of adult pancreatic neoplasms

- Age,Gender: children<<adults; peak incidence, 7th decade; M:F:: 4:1

- Prognosis and Therapy: directly related to tumor stage and is better than for ductal adenocarcinoma. Resection is treatment of choice.

- Radiological Features: Solid masses with well demarcated borders; rarely cystic

Key Cytological Features: Acinar Cell Carcinoma

- Solid-cellular smear pattern of monomorphic cells

- Cellular clusters of various sizes and single cells (loss of organoid "grape-like Clustering of benign acinar tissue)

- Stripped naked nuclei; +/- loose cytoplasmic granules (best noted on Hand E stain)

- May be disarmingly bland, with a polygonal cell shape and low N:C

- Coarse chromatin usually with prominent nucleoli, but not always granular cytoplasm, variably prominent

|

||

Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasm [SPN labeled slides]

- Incidence: ~1-3% of all pancreatic malignancies; 6% of exocrine tumors and ~24% of all surgically resected cystic lesions in the pancreas

- Age, Gender: ~90% women are in their 20’s; mean age is 28 years

- Prognosis and Therapy: Prognosis is excellent with only 15% developing recurrence or metastases

- Radiological Features: Well-circumscribed mass with solid and cystic components, usually in the pancreatic tail

Key Cytological Features: Solid-Pseudopapillary Neoplasm

- Solid cellular smear pattern with or without branching and papillary cell clusters

- Fibrovascular myxoid stromal papillae are characteristic Cells are relatively bland with little anisonucleosis and no mitotic activity

- Nuclei are round to oval with frequent nuclear grooves or focal indentations and finely granular chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli

- Cytoplasm is typically scant and ill-defined but can be moderate with small perinuclear vacuoles or intracytoplasmic hyaline globules, best detected on air-dried smears

- Smear background may be clean or filled with hemorrhagic cyst debris, foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells

|

||