Difference between revisions of "mgh:breast-Lobular Carcinoma Insitu (LCIS)"

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

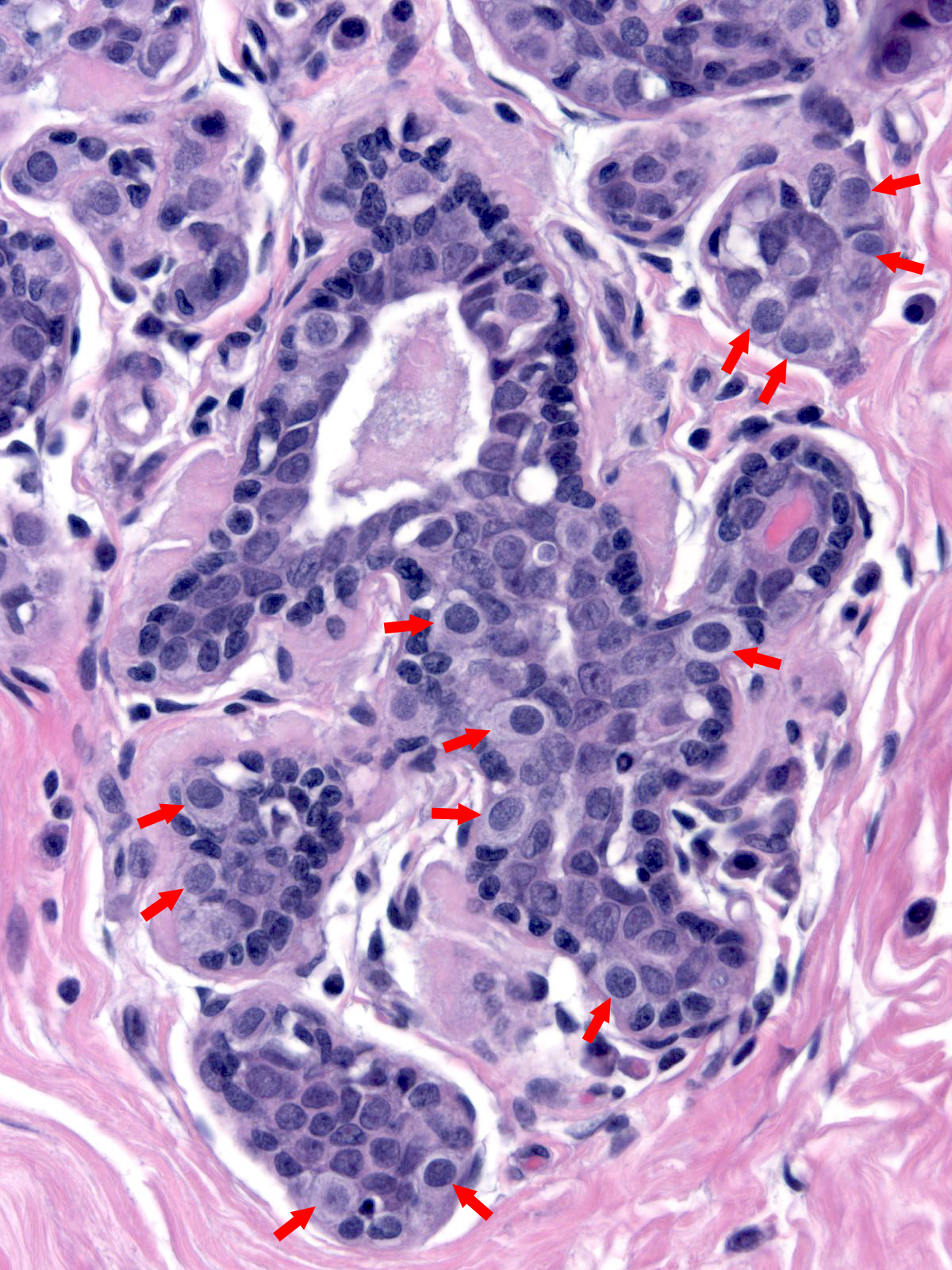

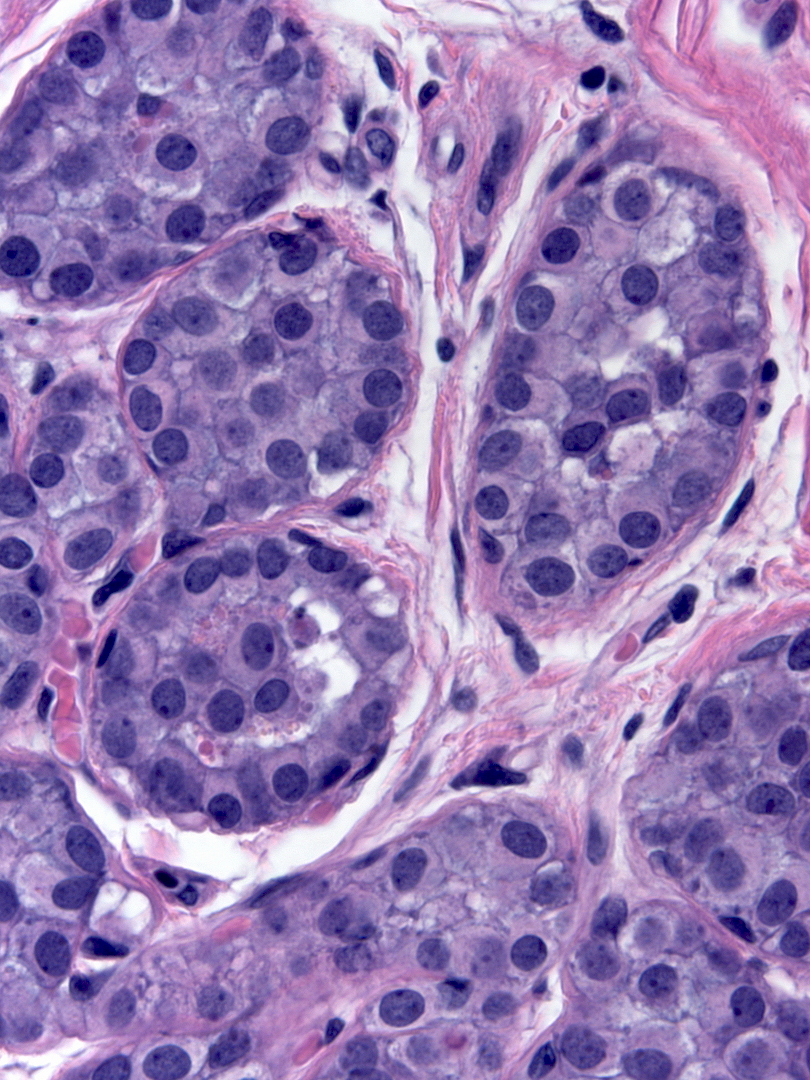

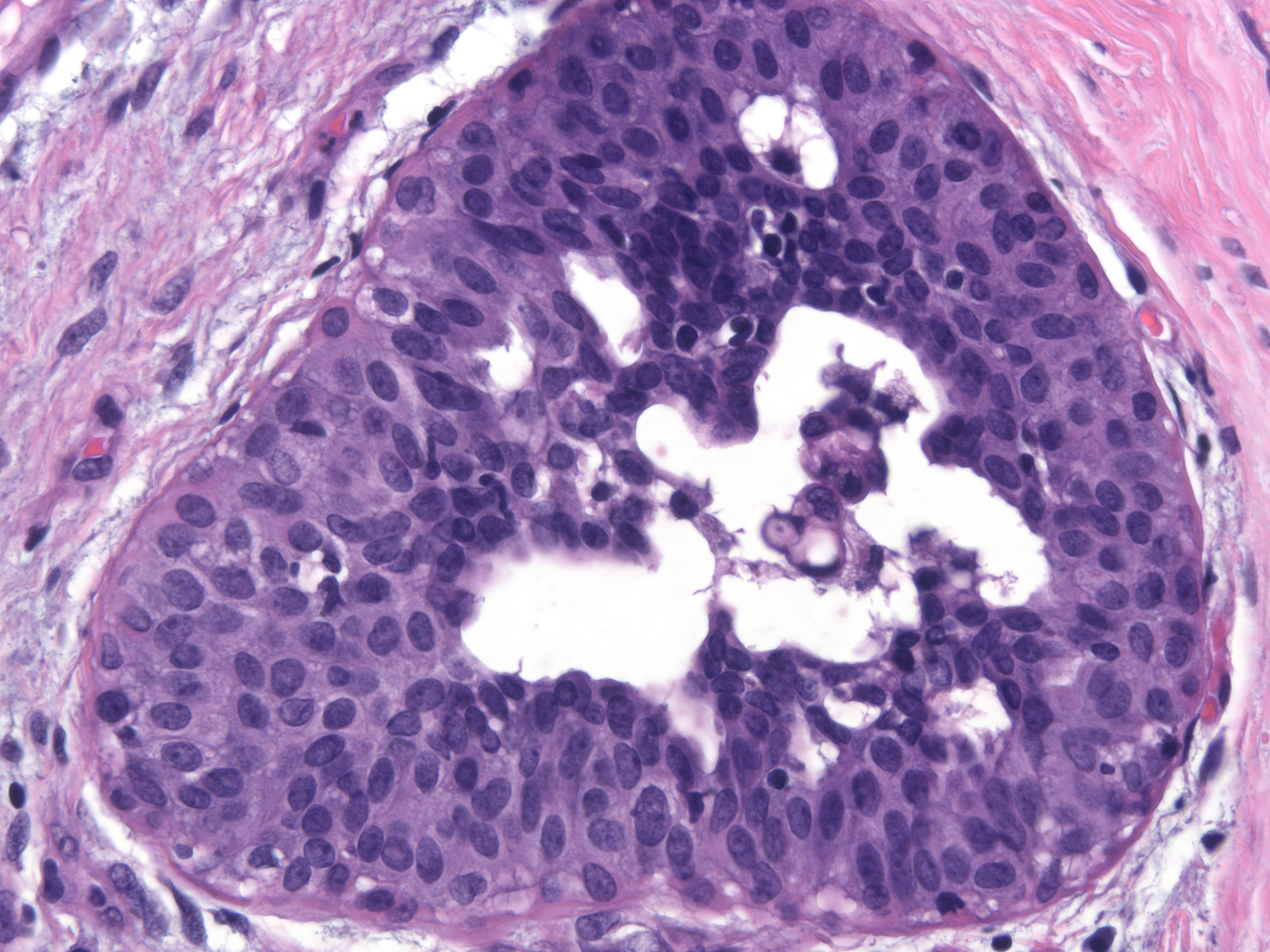

| − | {{dxintro|Lobular Carcinoma Insitu (LCIS)|Lobular neoplasia represents a neoplastic proliferation of atypical, dishesive, nonpolarized, epithelial cells growing in apparently discontinuous, scattered foci within the glandular tree. Pathologists divide lobular neoplasia into two categories based on the number of the neoplastic cells. Lobular carcinoma in-situ (LCIS) constitutes the more florid proliferation and atypical lobular hyperplasia the less pronounced version. The diagnosis of lobular carcinoma in-situ requires that characteristic neoplastic cells completely fill, distort, and distend at least 50% of the acini in a single lobule. Lesser involvement merits the diagnosis of atypical lobular hyperplasia. When the cells of lobular carcinoma in-situ display extreme pleomorphism, pathologists classify the lesion as pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in-situ.|Classic lobular carcinoma in-situ is an incidental finding; it does not appear on imaging nor does it produce clinical signs or symptoms. LCIS is typically multifocal and often bilateral. Because of this distribution, margin evaluation does not play a role in the pathological examination of specimens containing lobular carcinoma in-situ. Lobular carcinoma in-situ often co‑exists with other atypical mammary proliferations such as FEA, ADH, and low‑grade DCIS. Although LCIS represents the direct precursor to invasive lobular carcinoma, most subsequent invasive carcinomas in patients with LCIS are of ductal type. These invasive ductal carcinomas arise from foci of DCIS that co‑exist with the LCIS. The risk of developing invasive carcinoma is approximately 1% a year, and both breasts are equally at risk. When a core biopsy reveals the presence of lobular carcinoma in‑situ, a surgeon may carry out an excision of the biopsy site to exclude more serious malignancies. Radiologists at MGH usually recommend an excision, but the practice varies among institutions. The management of LCIS is complicated by its multicentric nature. Effective risk reduction requires either bilateral mastectomy or systemic hormonal therapy; however, since a majority of women with LCIS will never develop invasive carcinoma, long-term careful clinical follow-up and hormonal therapy are the prudent options.|None|Atypical, non-polarized, dishesive epithelial cells fill and distend acini, ductules, and ducts. Examples of classical lobular carcinoma in-situ do not display necrosis or mitotic activity.|Atypical lobular hyperplasia (few neoplastic cells), solid DCIS (more cohesive, polarized cells, positive E-cadherin), immature ductal hyperplasia (cohesive, blends with conventional usual hyperplasia), clear cell change (polarized, cohesive cells) (Clear cell change is a benign alteration in which the luminal cells in acini develop abundant, clear cytoplasm.)|Two fundamental properties characterize neoplastic lobular cells and distinguish them from other epithelial proliferations: dishesion, and lack of polarization. Dishesion prevents the neoplastic cells from attaching to their neighbors. Collections of dishesive cells appear loosely packed, and one can often observe small spaces between the cells within the aggregates. Among proliferative mammary epithelial cells, neoplastic lobular cells demonstrate the greatest degree of dishesion. One may have difficulty discerning the dishesion in uncommon cases. Neoplastic lobular cells virtually never demonstrate convincing polarity. Spaces may form within groups of neoplastic lobular cells, but the cells surrounding the spaces do not demonstrate polarization.| | + | {{dxintro|Lobular Carcinoma Insitu (LCIS)|Lobular neoplasia represents a neoplastic proliferation of atypical, dishesive, nonpolarized, epithelial cells growing in apparently discontinuous, scattered foci within the glandular tree. Pathologists divide lobular neoplasia into two categories based on the number of the neoplastic cells. Lobular carcinoma in-situ (LCIS) constitutes the more florid proliferation and atypical lobular hyperplasia the less pronounced version. The diagnosis of lobular carcinoma in-situ requires that characteristic neoplastic cells completely fill, distort, and distend at least 50% of the acini in a single lobule. Lesser involvement merits the diagnosis of atypical lobular hyperplasia. When the cells of lobular carcinoma in-situ display extreme pleomorphism, pathologists classify the lesion as pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in-situ.|Classic lobular carcinoma in-situ is an incidental finding; it does not appear on imaging nor does it produce clinical signs or symptoms. LCIS is typically multifocal and often bilateral. Because of this distribution, margin evaluation does not play a role in the pathological examination of specimens containing lobular carcinoma in-situ. Lobular carcinoma in-situ often co‑exists with other atypical mammary proliferations such as FEA, ADH, and low‑grade DCIS. Although LCIS represents the direct precursor to invasive lobular carcinoma, most subsequent invasive carcinomas in patients with LCIS are of ductal type. These invasive ductal carcinomas arise from foci of DCIS that co‑exist with the LCIS. The risk of developing invasive carcinoma is approximately 1% a year, and both breasts are equally at risk. When a core biopsy reveals the presence of lobular carcinoma in‑situ, a surgeon may carry out an excision of the biopsy site to exclude more serious malignancies. Radiologists at MGH usually recommend an excision, but the practice varies among institutions. The management of LCIS is complicated by its multicentric nature. Effective risk reduction requires either bilateral mastectomy or systemic hormonal therapy; however, since a majority of women with LCIS will never develop invasive carcinoma, long-term careful clinical follow-up and hormonal therapy are the prudent options.|None|Atypical, non-polarized, dishesive epithelial cells fill and distend acini, ductules, and ducts. Examples of classical lobular carcinoma in-situ do not display necrosis or mitotic activity.|Atypical lobular hyperplasia (few neoplastic cells), solid DCIS (more cohesive, polarized cells, positive E-cadherin), immature ductal hyperplasia (cohesive, blends with conventional usual hyperplasia), clear cell change (polarized, cohesive cells) (Clear cell change is a benign alteration in which the luminal cells in acini develop abundant, clear cytoplasm.)|Two fundamental properties characterize neoplastic lobular cells and distinguish them from other epithelial proliferations: dishesion, and lack of polarization. Dishesion prevents the neoplastic cells from attaching to their neighbors. Collections of dishesive cells appear loosely packed, and one can often observe small spaces between the cells within the aggregates. Among proliferative mammary epithelial cells, neoplastic lobular cells demonstrate the greatest degree of dishesion. One may have difficulty discerning the dishesion in uncommon cases. Neoplastic lobular cells virtually never demonstrate convincing polarity. Spaces may form within groups of neoplastic lobular cells, but the cells surrounding the spaces do not demonstrate polarization.|13-1 Dishesion.jpg|These LCIS cells appear to separate from one another. Adrift, they show no consistent orientation with respect to either the basement membrane or the acinar lumen.}} |

== Lack of Polarization == | == Lack of Polarization == | ||

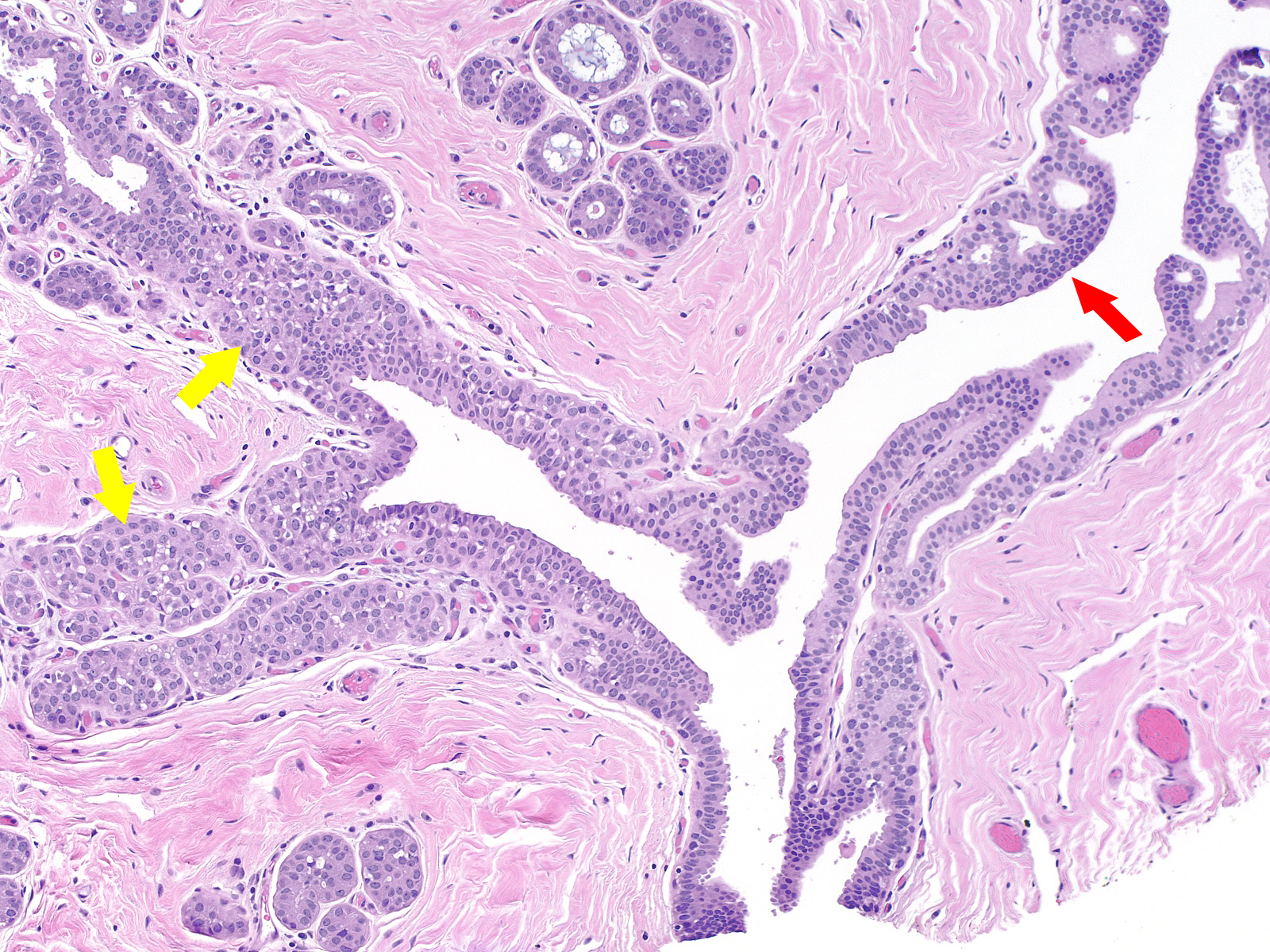

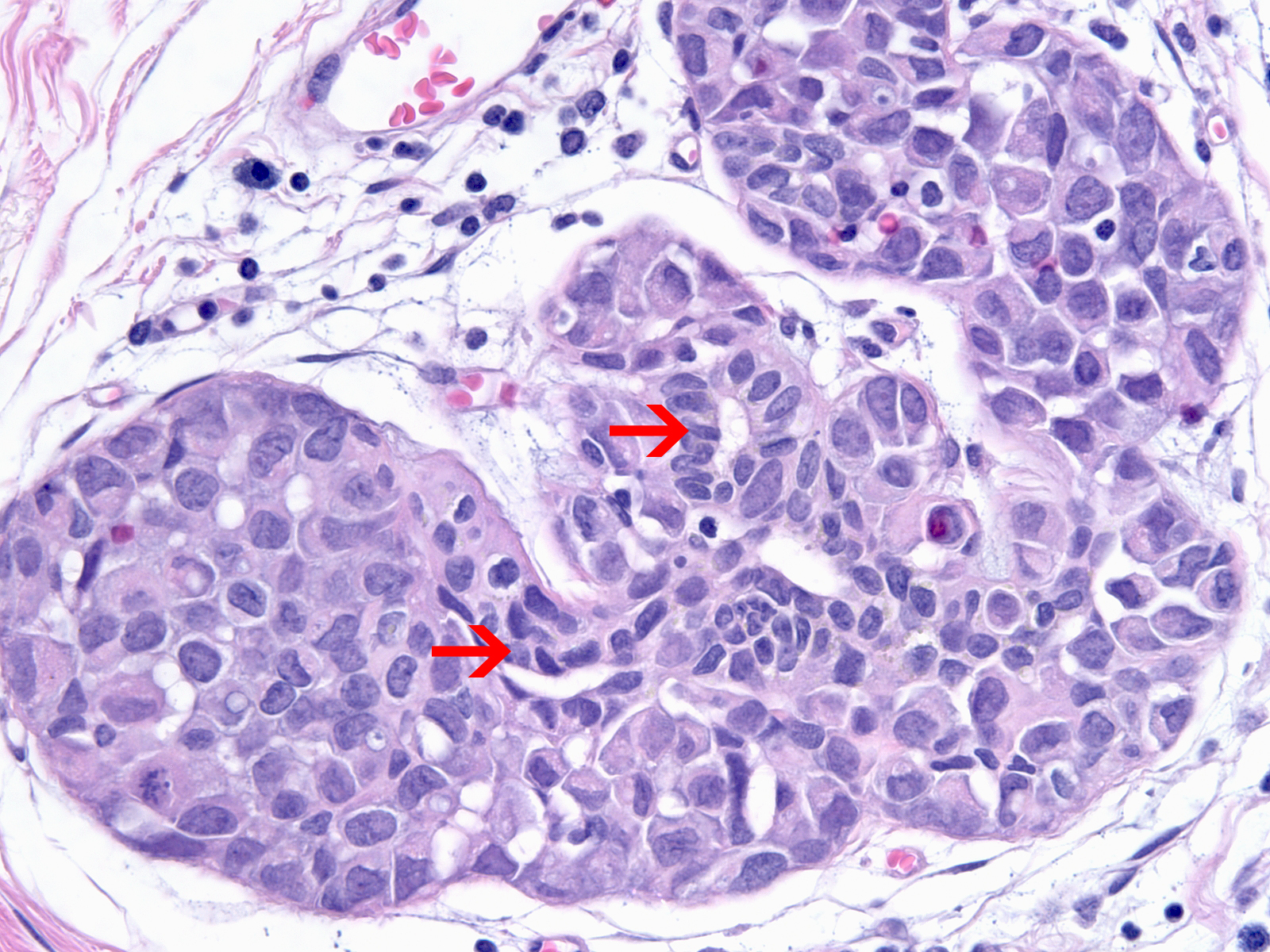

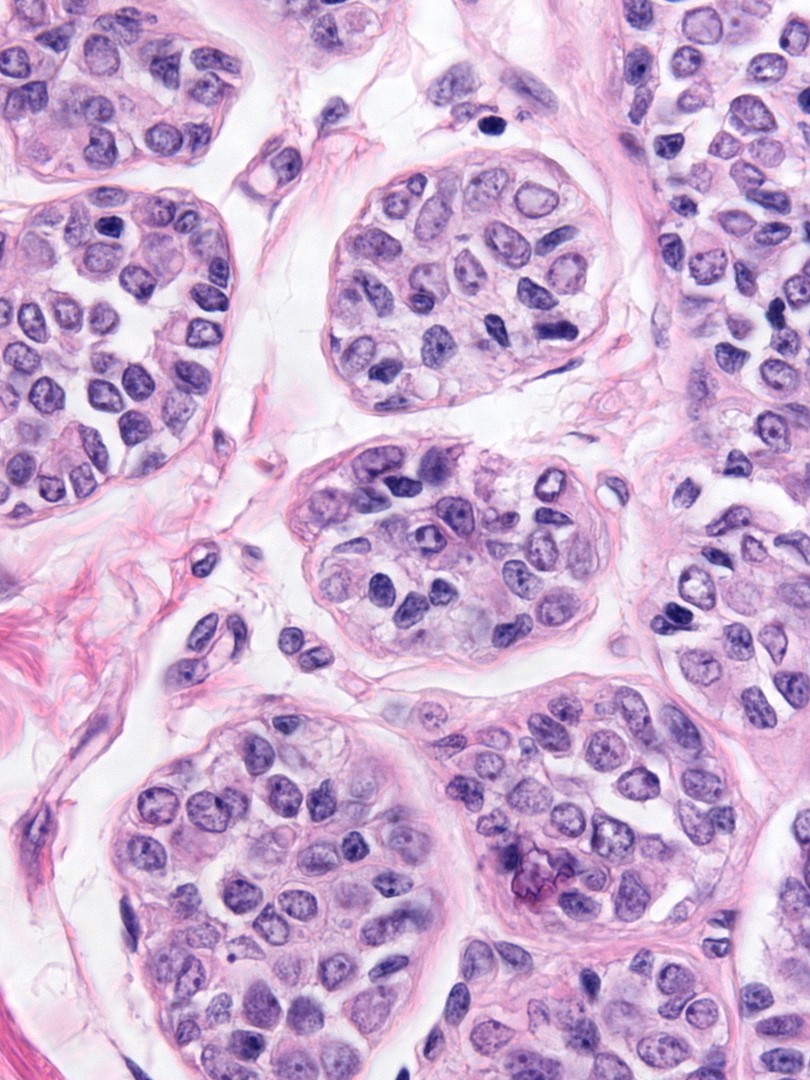

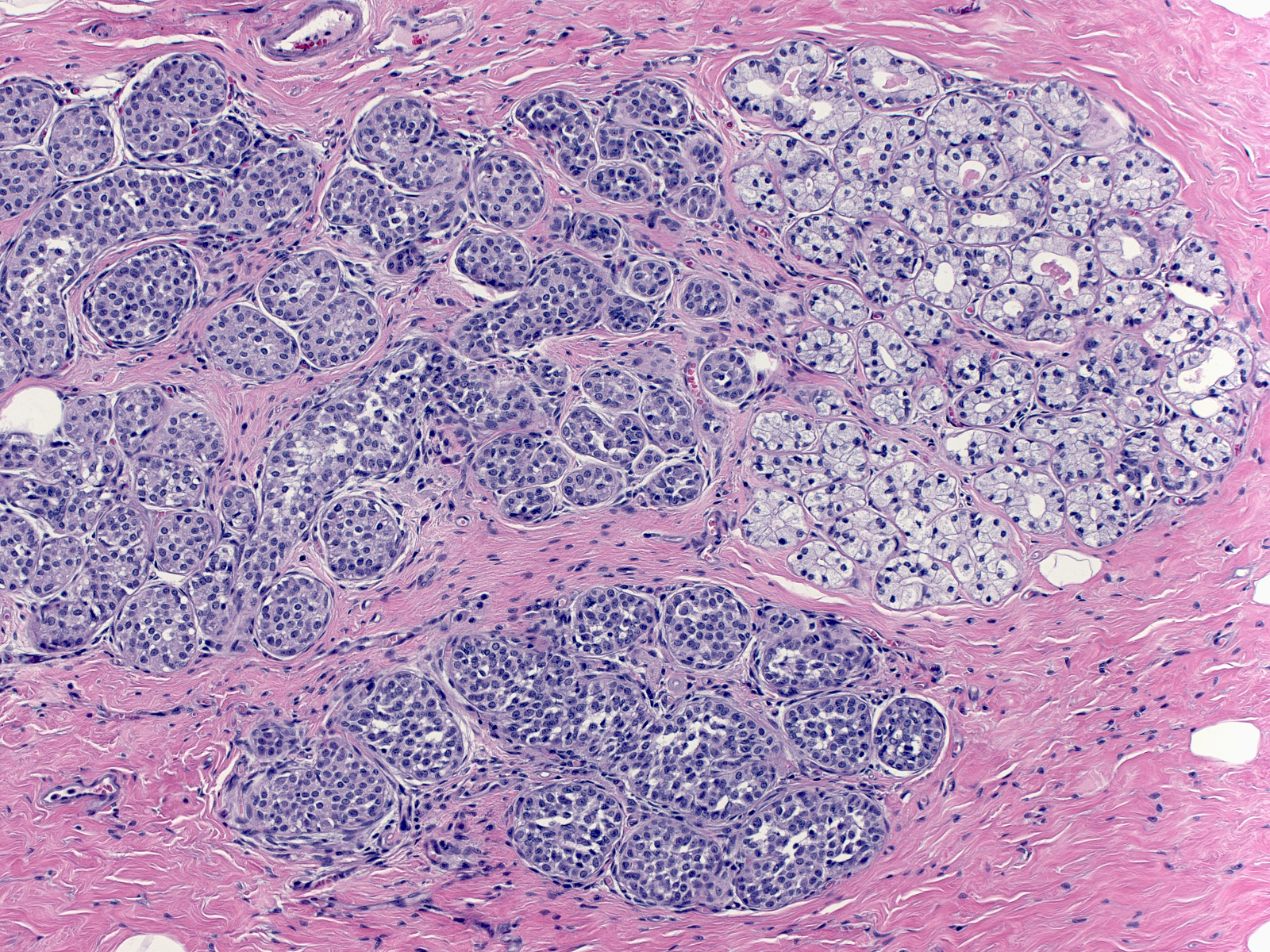

{{img1|Normal epithelial cells rely on their attachment to the basement membrane and/or surrounding cells in order to establish polarity. It is therefore understandable that in lobular neoplasia the property of dishesion coincides with a lack of polarity. This image contains both neoplastic lobular and neoplastic ductal cells.|13-2 Low_power_w_arrows.jpg}} | {{img1|Normal epithelial cells rely on their attachment to the basement membrane and/or surrounding cells in order to establish polarity. It is therefore understandable that in lobular neoplasia the property of dishesion coincides with a lack of polarity. This image contains both neoplastic lobular and neoplastic ductal cells.|13-2 Low_power_w_arrows.jpg}} | ||

Latest revision as of 08:02, July 17, 2020

Contents

Introduction

|

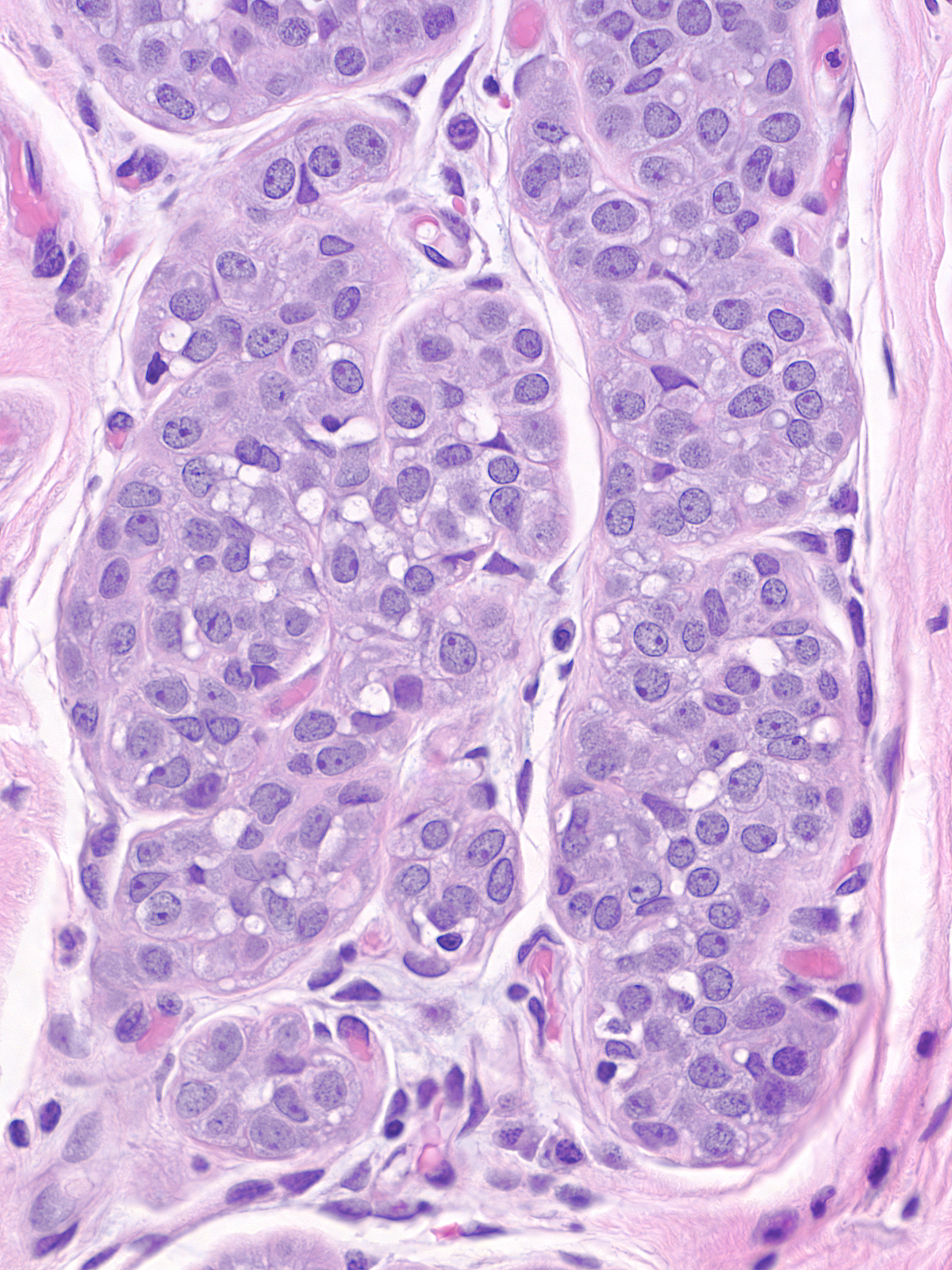

Definition: Lobular neoplasia represents a neoplastic proliferation of atypical, dishesive, nonpolarized, epithelial cells growing in apparently discontinuous, scattered foci within the glandular tree. Pathologists divide lobular neoplasia into two categories based on the number of the neoplastic cells. Lobular carcinoma in-situ (LCIS) constitutes the more florid proliferation and atypical lobular hyperplasia the less pronounced version. The diagnosis of lobular carcinoma in-situ requires that characteristic neoplastic cells completely fill, distort, and distend at least 50% of the acini in a single lobule. Lesser involvement merits the diagnosis of atypical lobular hyperplasia. When the cells of lobular carcinoma in-situ display extreme pleomorphism, pathologists classify the lesion as pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in-situ. Clinical Significance: Classic lobular carcinoma in-situ is an incidental finding; it does not appear on imaging nor does it produce clinical signs or symptoms. LCIS is typically multifocal and often bilateral. Because of this distribution, margin evaluation does not play a role in the pathological examination of specimens containing lobular carcinoma in-situ. Lobular carcinoma in-situ often co‑exists with other atypical mammary proliferations such as FEA, ADH, and low‑grade DCIS. Although LCIS represents the direct precursor to invasive lobular carcinoma, most subsequent invasive carcinomas in patients with LCIS are of ductal type. These invasive ductal carcinomas arise from foci of DCIS that co‑exist with the LCIS. The risk of developing invasive carcinoma is approximately 1% a year, and both breasts are equally at risk. When a core biopsy reveals the presence of lobular carcinoma in‑situ, a surgeon may carry out an excision of the biopsy site to exclude more serious malignancies. Radiologists at MGH usually recommend an excision, but the practice varies among institutions. The management of LCIS is complicated by its multicentric nature. Effective risk reduction requires either bilateral mastectomy or systemic hormonal therapy; however, since a majority of women with LCIS will never develop invasive carcinoma, long-term careful clinical follow-up and hormonal therapy are the prudent options. Gross Findings: None Microscopic Findings: Atypical, non-polarized, dishesive epithelial cells fill and distend acini, ductules, and ducts. Examples of classical lobular carcinoma in-situ do not display necrosis or mitotic activity. Differential Diagnosis: Atypical lobular hyperplasia (few neoplastic cells), solid DCIS (more cohesive, polarized cells, positive E-cadherin), immature ductal hyperplasia (cohesive, blends with conventional usual hyperplasia), clear cell change (polarized, cohesive cells) (Clear cell change is a benign alteration in which the luminal cells in acini develop abundant, clear cytoplasm.) Discussion: Two fundamental properties characterize neoplastic lobular cells and distinguish them from other epithelial proliferations: dishesion, and lack of polarization. Dishesion prevents the neoplastic cells from attaching to their neighbors. Collections of dishesive cells appear loosely packed, and one can often observe small spaces between the cells within the aggregates. Among proliferative mammary epithelial cells, neoplastic lobular cells demonstrate the greatest degree of dishesion. One may have difficulty discerning the dishesion in uncommon cases. Neoplastic lobular cells virtually never demonstrate convincing polarity. Spaces may form within groups of neoplastic lobular cells, but the cells surrounding the spaces do not demonstrate polarization. |

|

Lack of Polarization

| Normal epithelial cells rely on their attachment to the basement membrane and/or surrounding cells in order to establish polarity. It is therefore understandable that in lobular neoplasia the property of dishesion coincides with a lack of polarity. This image contains both neoplastic lobular and neoplastic ductal cells. |  |

A collision of neoplastic lobular cells (yellow) with neoplastic ductal cells (red)

Contrast the dishesion and lack of polarity of the neoplastic lobular cells (left) with the cohesion and polarization of the neoplastic ductal cells (right).

|

|

Origin and Progression

Neoplastic lobular cells first make their appearance along the basement membrane and within the epithelium of acini, ductules, and ducts.

|

|

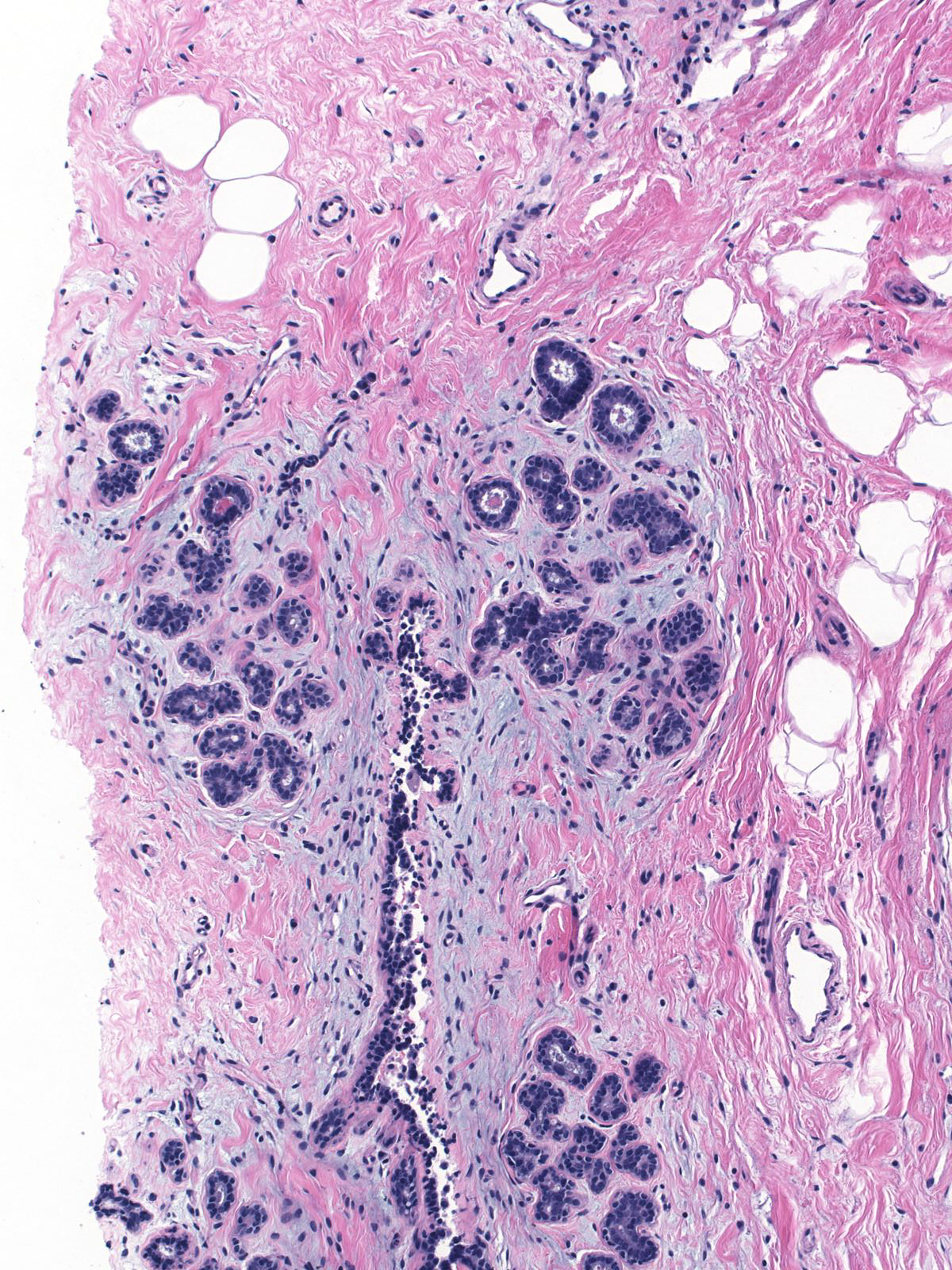

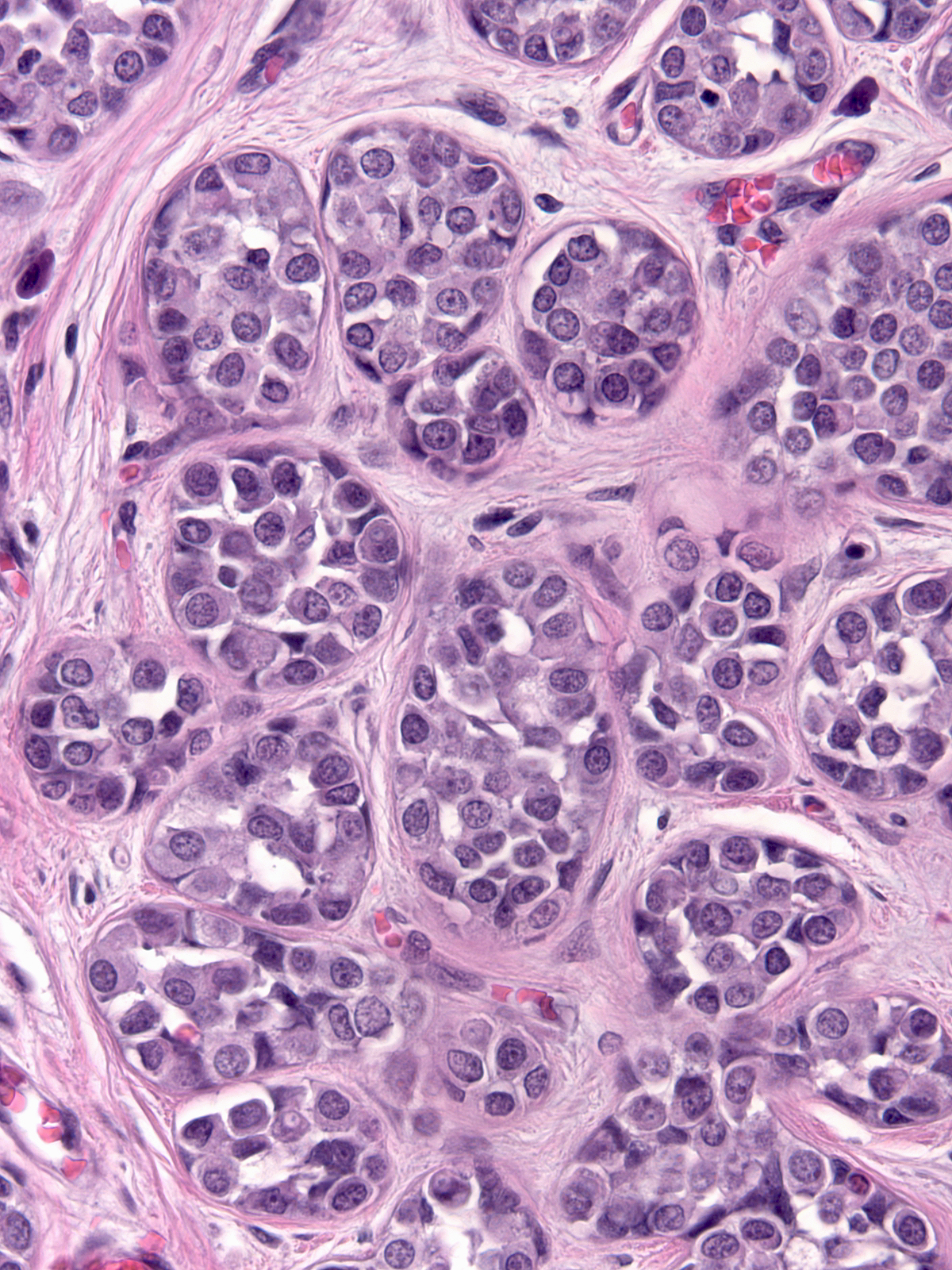

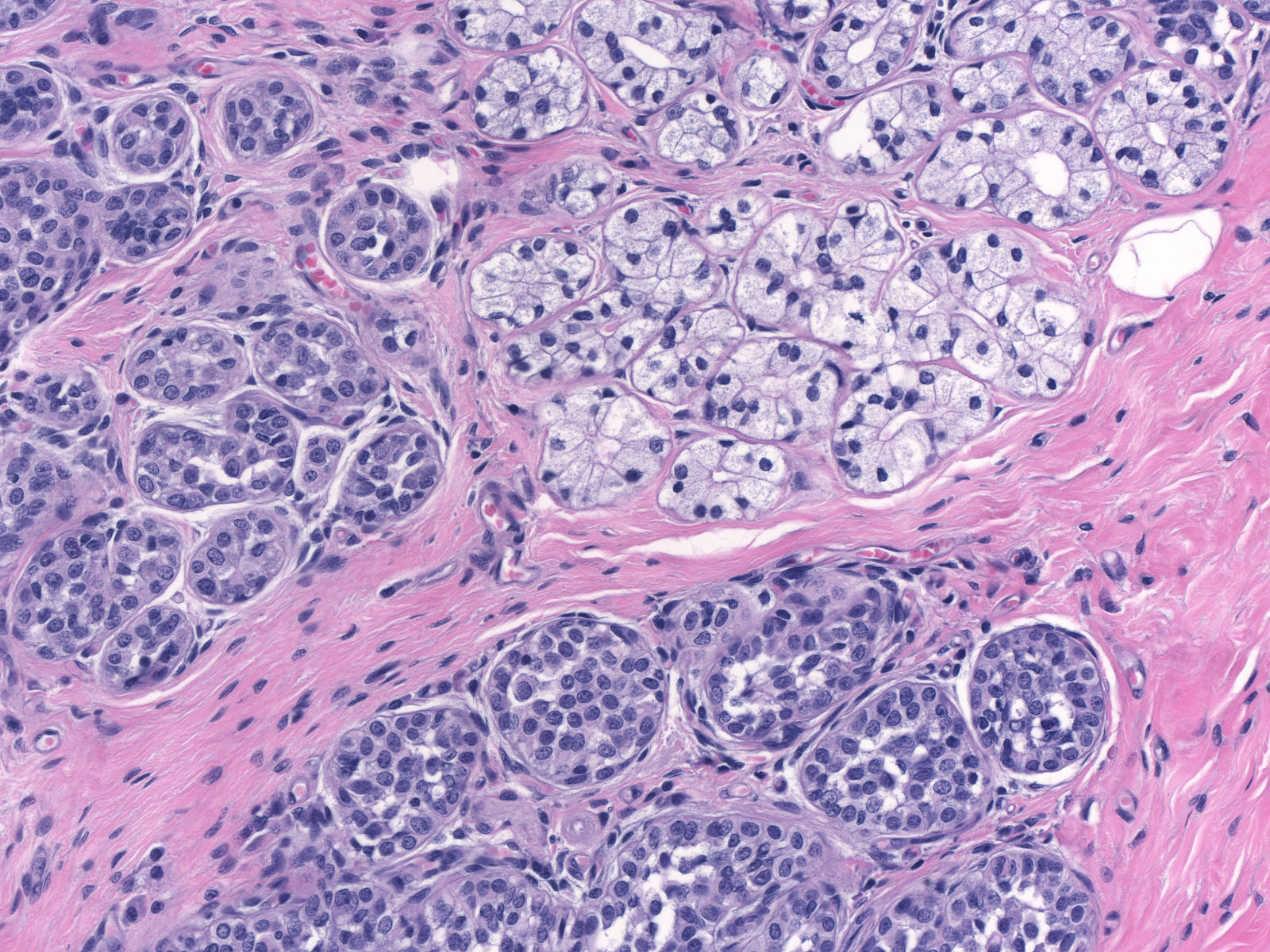

| As the neoplastic cells accumulate, they displace pre-existing luminal and myoepithelial cells. The displaced luminal epithelial cells (?) are recognizable by their small size, tight cohesion, and retained polarity. |  |

Eventually the neoplastic cells fill and distend the acini. Contrast the size and apparent number of acini in the uninvolved lobules (left) with those of the lobules overrun by LCIS (right). Both images were taken at the same power.

|

|

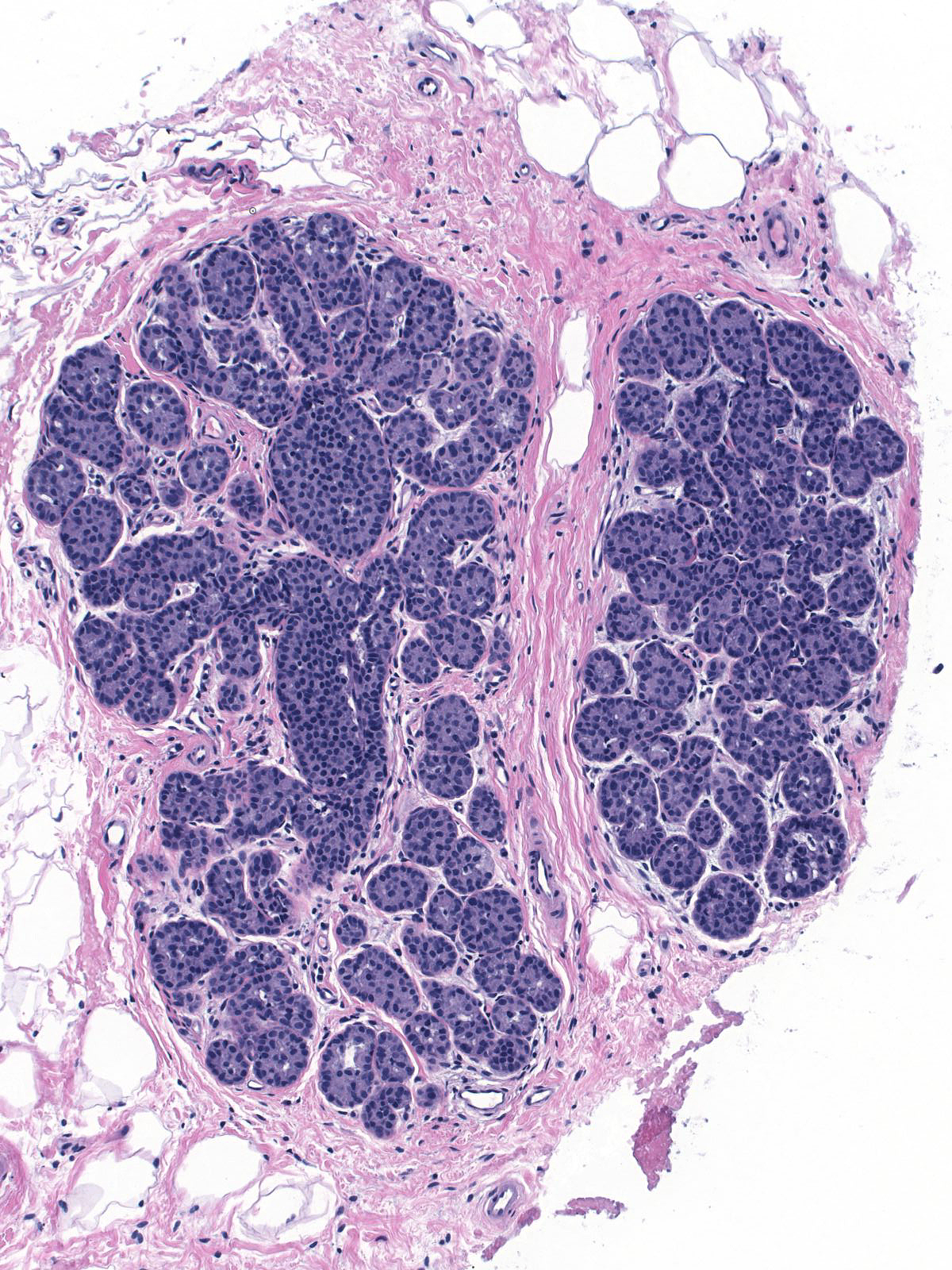

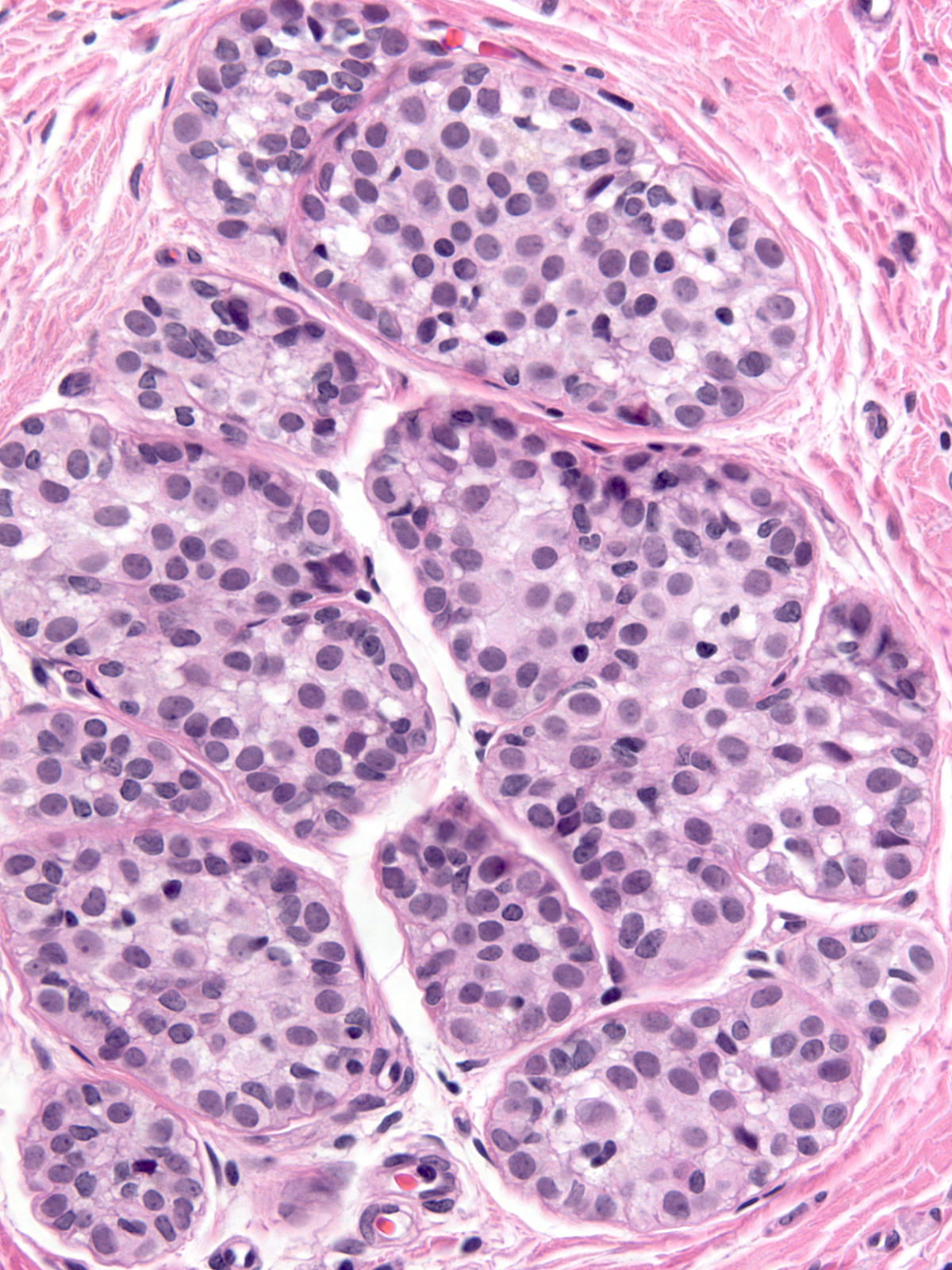

| Often, the acini assume odd shapes, and, in certain cases, the number of acini composing the lobules seems increased. (Bulbous expansion of acini by LCIS cells) |  |

| The affected acini expand and become closely packed. As a result, the intralobular stroma may become attenuated. |  |

| In uncommon examples, the specialized stroma demonstrates reactive changes. |  |

Cytology

| Neoplastic lobular cells vary only slightly from one case to the next, and the cells within a given case look uniform. They appear slightly larger than their normal counterparts and they possess slightly larger nuclei and slightly more abundant cytoplasm.(LCIS cells alongside compressed residual luminal cells) |  |

The nuclei may have oval or round shapes and smooth contours (left), but much more often the nuclei appear slightly deformed and irregular in contour (right).

|

|

The chromatin can appear either granular and pale (left) or homogeneous and dark (right). Many nuclei contain small nucleoli.

|

|

| The cytoplasm stains faintly eosinophilic or amphophilic and it often contains miniscule mucin vacuoles of mucin, which give it a foamy quality.13-18 Foamy.jpg | |

| Sometimes the mucin aggregates and displaces the nucleus, forming a signet ring cell. |  |

| In certain examples of LCIS, the cells contain spaces lined by microvilli. Although reminiscent of signet ring cells, these spaces represent intracytoplasmic lumens rather than collections of mucin. |  |

In occasional cases of lobular carcinoma in‑situ, the cells appear larger than those seen in typical lobular neoplasia. The nuclei and nucleoli in these uncommon cases also appear larger and demonstrate greater pleomorphism than one typically observes; however, these alterations do not appear sufficiently extreme to warrant a diagnosis of pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in‑situ. Pathologists refer to this constellation of cytological findings as the Haagensen Type B pattern.

|

|

Calcifications

The neoplastic cells do not form calcifications, but they can engulf those formed in pre-existing conditions such as fibrocystic changes and sclerosing adenosis.

|

|

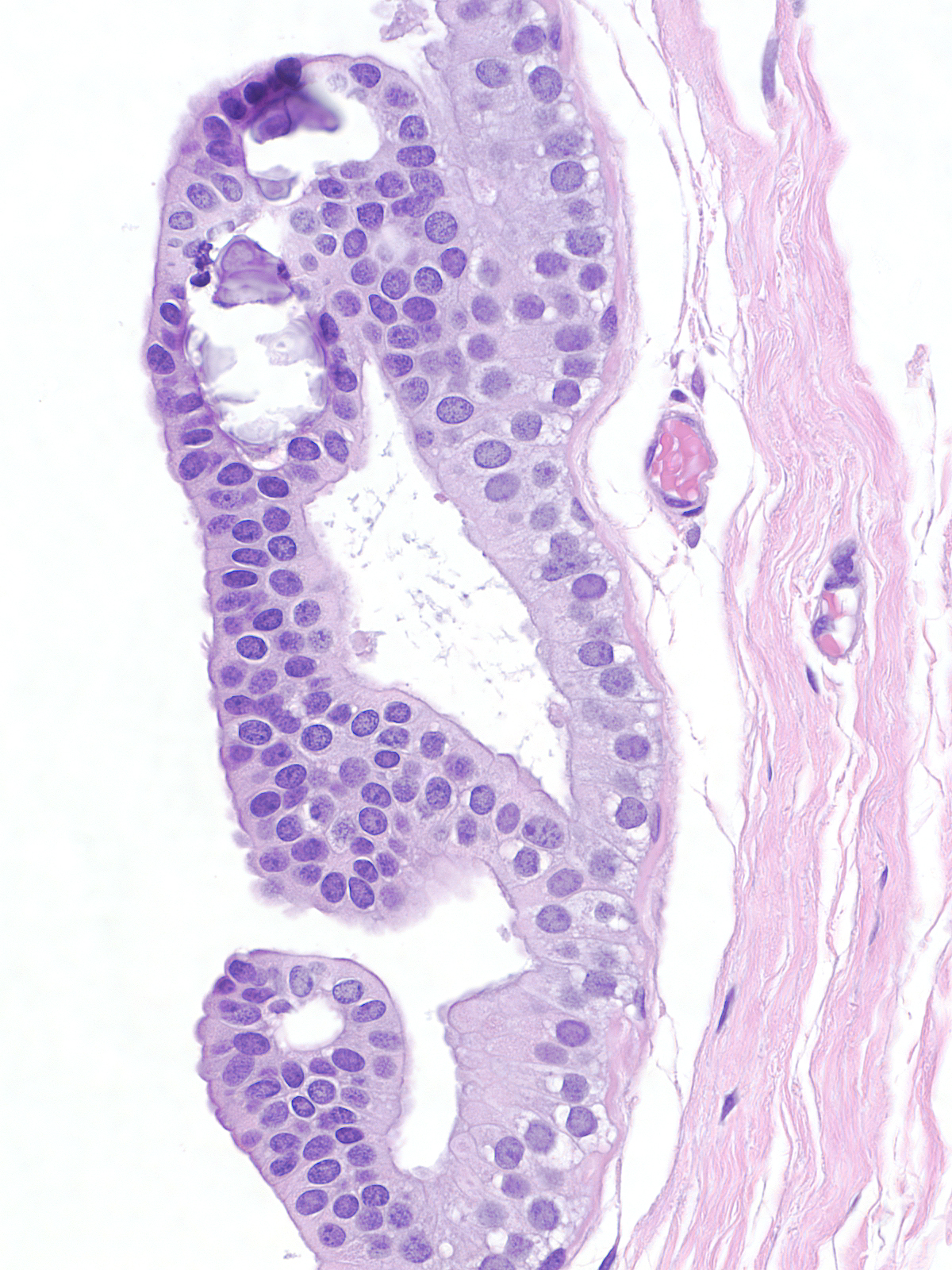

Involvement of Ducts

Besides affecting lobules, lobular carcinoma in-situ often involves ducts. Proliferation in ducts can create three patterns.

| 1. In the most common pattern, referred to as pagetoid spread, the neoplastic cells accumulate beneath the pre-existing luminal cells, which remain in a single, flattened layer. (Pagetoid spread of LCIS) |  |

Irregular pagetoid involvement of the epithelium results in unusual architectural patterns such as complex fenestrated collections (left) and pseudopapillary formations (right).

|

|

| 2. In florid proliferations within ducts, the indigenous luminal cells disappear entirely and the neoplastic lobular population forms a loosely cohesive mass occupying most of the lumen. Central necrosis and calcification can occur in these masses. (Florid LCIS filling a duct) |  |

| 3. Finally, small buds in the walls of large ducts can also harbor neoplastic lobular cells. (LCIS cells filling small buds in the wall of a large duct) |  |

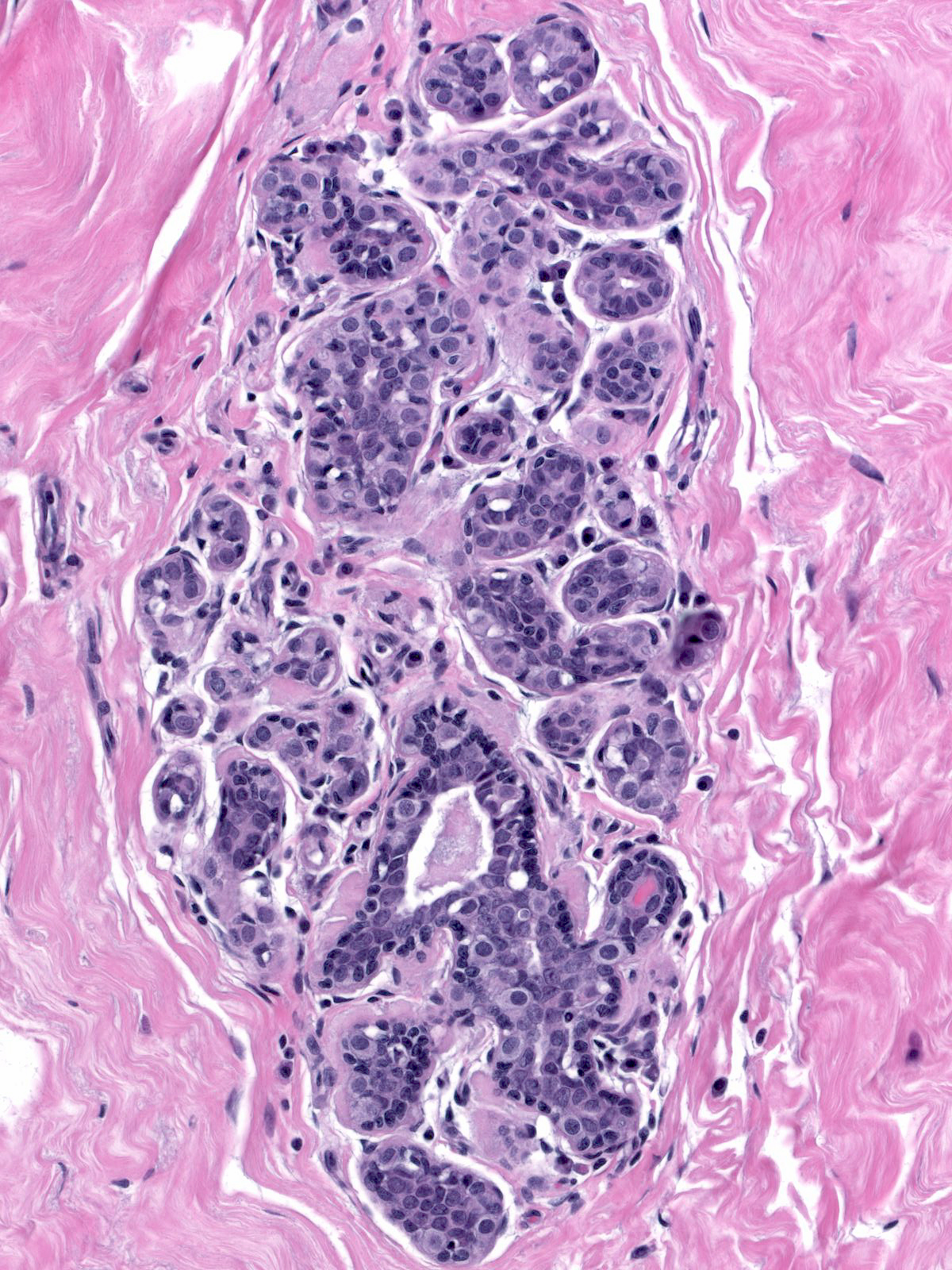

Involvement of Other Lesions

Neoplastic lobular cells can inhabit glandular tissue altered by unrelated benign lesions such as sclerosing adenosis (left), collagenous spherulosis (middle), and radial scars (right). The combination of the atypia of the neoplastic cells and the architecture of the underlying lesion may mimic the appearance of another lesion. For example, LCIS involving collagenous spherulosis shares many features with DCIS and LCIS involving sclerosing adenosis or the central part of a radial scar may look like an invasive carcinoma.

|

|

|

Neoplastic lobular cells can also involve epithelial proliferations such as usual ductal hyperplasia (left) and ductal carcinoma in-situ (right). Immunohistochemical stains usually help to identify the underlying lesion.

|

|

| Lobular carcinoma in-situ often co-exists with the other lesions in the low-grade carcinoma cluster: flat epithelial atypia, atypical ductal hyperplasia, and atypical apocrine hyperplasia. (LCIS beneath an acinus distended by flat epithelial atypia) |  |

Staining for E-cadherin

| The cells of lobular neoplasia do not stain for E-cadherin; however, luminal and myoepithelial cells express the protein, and the mingling of the cells often produces difficult to understand staining results. This image is relatively easy to interpret. (Staining for E-cadherin is absent between the LCIS cells stuffing these acini.) |  |

The mingling of neoplastic lobular cells with indigenous epithelial cells or with hyperplastic epithelial cells gives rise to complex staining results, which prove more challenging to interpret.

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Distinguishing lobular carcinoma in-situ from solid low-grade DCIS represents a formidable problem. The presence of polygonal cells with clearly defined cell borders and angular contours, the absence of dishesion, and the presence of subtle evidence of cellular polarization favor the diagnosis of DCIS rather than LCIS; however, many cases do not demonstrate these findings. Staining for E-cadherin offers definitive evidence as to the nature of the neoplastic cells.

|

|

|

| One can confuse lobular carcinoma in-situ with ductal hyperplasia composed of large cells thought to represent immature hyperplastic ductal cells. (Immature ductal hyperplasia) |  |

| The basally situated cells of immature ductal hyperplasia grow in cohesive clusters or layers. They have round to oval nuclei, homogeneous or finely granular chromatin, small nucleoli, and ample cytoplasm, which varies from finely granular and eosinophilic to pale. (Immature ductal hyperplasia) |  |

| Immature hyperplastic ductal cells do not display the dishesion that characterizes neoplastic lobular cells. (Lobular neoplasia (left duct) and immature ductal hyperplasia (right duct)) |  |

| Immature ductal hyperplasia usually blends with conventional ductal hyperplasia |  |

| Clear cell change is another benign alteration that one might confuse with lobular neoplasia. Clear cell change typically affects acinar cells, and causes their cytoplasm to become especially clear. (Lobular neoplasia (left) and clear cell change (top right)) |  |

| Cells showing clear cell change (top right) appear polarized and cohesive and they possess bland nuclei and abundant clear cytoplasm. These features contrast with those of neoplastic lobular cells (left and bottom). |  |